All posts by Mark Wilson

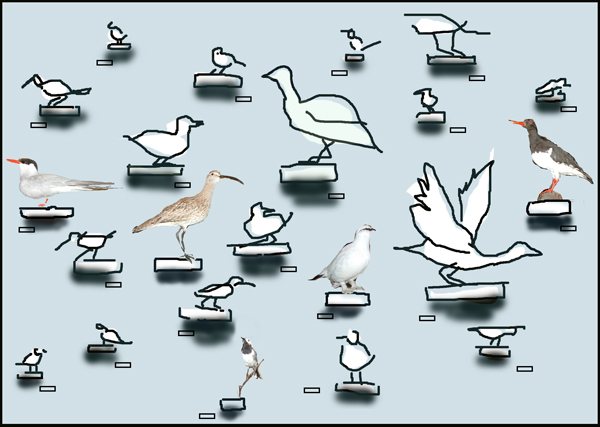

Íslenskir Fuglar

For Íslenskir Fuglar we look at human ambivalence regarding ideas of change. On the one hand we are conservative and suspicious of the disruption that change inevitably means. On the other we are drawn both to spice and novelty and to the practical benefits that some new introductions to our lives can bring. The judgment we make here between what we consider to be manageable and controllable and what we deem to be too disruptive and problematic is one that is fraught with potential miscalculations and unseen ramifications.

Long-term ramifications, touch at least obliquely, on the ecological and environmental consequences of human taste, fashion and favouritism – see for instance Mark Dion’s Survival of the Cutest –and this albeit wider interpretation is another reasonable reading of Islenskir Fuglar.

Commissioned for the exhibition Bæ Bæ Iceland (2007) the artists considered issues of nationality and nationhood, particularly in relation to changing populations. Iceland has traditionally fostered notions of cultural purity and defiance in relation to language, the economy, customs and identity. Despite this, in the most unexpected quarters small, incremental allowances, unnoticed over the years, have created new sub-cultures that when considered together cannot help but be seen as constituting an assault on ideas of cultural permanence or immutability.

Something as apparently beneficial and reliable as a map or a guide, if it is to remain of any use must take into account these small changes and therefore over time will come to be a barometer of larger cultural shifts – it must be a document of how we present ourselves, practically and symbolically both to ourselves and to the visitor. Any map or guide designed to reflect the state of things must in these circumstances be subject to a programme of regular updates. It is by these means that we present ourselves, practically and symbolically both to ourselves and to the visitor, but increasingly this will be a snapshot rather than a lasting document.

In attempting to identify what has changed in us but what still may help to define the new ‘us’ it’s possible that paradoxically, we may usefully examine our taste for the exotic. By comparing the old with new representations it should be possible to gauge the larger cultural shifts and trends that have occurred and anticipate those that may yet come to pass. In this we can measure our tastes and desires. Fashions come and go but some desires will stand the test of time – are assimilated by us and come to permanently shape the way we see ourselves and the way we are seen by others. Definitions are meant to be definitive. What is definitive today however, may no longer be definitive tomorrow and in this work, Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson are particularly interested in speculatively re-configuring the parameters upon which such definitions might be drawn. It is an innocuous game but one with the potential to nibble at, erode and disturb the borders of past, present and future, of local and global, natural and cultural, of acceptability and taboo.

Exhibited at; Bæ, Bæ Iceland, Listasafn Akureyrar, Iceland (2007) Inbetween: Cabinet of Curiousities, Hafnarborg, Iceland (2011)

Promised Land: ecologies of uncertainty

Radio Animal

Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson: Radio Animal Unit

The mechanism of the mobile unit itself was extremely successful. People entered the caravan, sat down and were put at their ease, very often remarking how comfortable it was. This sense of comfort and intimacy was constructively disarming and such a commitment would always yield at least one if not several stories.

By these two means – our excursions with Pest Control operatives and the Radio Animal interviews we fielded and recorded hundreds of accounts of animal/human encounters, and by so doing, a picture began to emerge of local human behaviour towards animals and the environment—of tolerance and intolerance, of fear and loathing, affection, conflict, pathos, admiration, longing and so on.

home

Animal Matters

Galleri Sverdrup, Georg Sverdrups hus, Blindern, Oslo. 11 May to 24 August 2012

When Liv Emma Thorsen offered us the opportunity to work with a team of academics engaged in a research project exploring “what is an animal?” its possibilities seemed tantalizingly irresistable. Through our own work we were already familiar with a number of the participants and on familiarizing ourselves further with all the research specific to this project, the respective papers, and consequent conversation through correspondence, we found the content sitting surprisingly close to our own concerns and artwork. As artists whose practice engages with human/animal relations and what they reveal about ourselves and our relationship to the environment, the question of representation – who speaks for whom? – is paramount. To translate a thought into an object, (and here it is hoped, objects into thoughts) and for it to carry particular meanings, also raises questions that are topical in the context of academia and artistic research. In our own artwork, relationality is of particular importance and in our contribution to this project we acknowledge and it is hoped, expose a complex web of meaning accretion. Significant resonance is present for instance within the narrative microcosm of each exhibit. In turn, it exists between all the exhibits, between the objects, the gallery space and their institutional context here and between these components and the specific wordling of the visitor to this exhibition. Here, discrete histories well up refreshingly from ancient artefacts and are revealed as subjective, intimate. As such they remind us that knowledge is always subject to revision and history can tell us not only why we are what we are today, but how else we can be.Animal Matters is a project residing somewhere between curatorial practice and the practice of art, leading amongst other productions including a book, to an exhibition in The Svedrup Galleri at the University of Oslo. This exhibition involved a collaboration with nine academics and their research arising from a number of discrete fields across the humanities and sciences.

As artists whose research-based practice engages strategically with human-animal relations and what these can reveal about our behaviour and our relationship to the environment, the question of representation – who is speaking for whom – is crucial. To translate a thought into an object, for it to carry a particular meaning also carries with it questions that are topical in the context of academia and artistic research. In our artwork, relationality is of great importance. It’s in the connection between things – for instance the objects in the exhibition – the objects and the exhibition space – the objects and the context of the exhibition – between part or all of these components and/or the worlding of the visitor to this exhibition – that the meanings are generated and take shape. In those moments of encounter, a shift in thinking is made possible. In that shift – in that destabilising, a door opens and beyond it, lies the possibility of new knowledge and of behavioural change

It is in the unreliability of objects that we find the significance of any display productively unstable, in flux and capable of offering not one but a multitude of narratives – by the removal of this or the addition of that – never individually to be trusted as conclusive. In this project therefore, it was in this precarious dynamic and the potentialities of an array of juxtaposed narratives, arcing between each other, that the fascination and the challenge lay.

So with this in mind there were many factors to consider in respect of the work of each of the nine researchers involved, Brian Ogilvie, Karen Rader, Siv Berg, Guro Flinterud, Nigel Rothfels, Brita Brenna , Adam Dodd, Liv Emma Thorsen, Henry McGhie.

Initially for us as artists, the task also raised questions relating to ownership and autonomy. In some senses we were approaching the project not only as artists but as curators – of material yes, but also of ideas. We say initially because these questions were soon put aside and we did rather plunge in with a degree of confidence concerning what would most certainly evolve. We mentioned already the issue of relationality, as being of high importance during the process of development in our artwork and indeed in our installation work. To evoke this relationality through disparate objects and to prime the potential conversation between a variety of assemblages requires an understanding also of spatial relations and how these relations might be usefully activated.

Our artwork critiques the flawed application of representations (and animal representations in particular) – conveniences we have become accustomed to digesting without thinking. We take these representations as they appear within the context of art, popular culture and historical collections and by a process of often seemingly slight adjustment or careful juxtaposition, we shift a balance within pre-coded framings of the ‘image’. It is within the second, longer look by the viewer, this prompt to think again and in the resultant space of unexpected affect (humour, dissonance, surprise) that the art functions.

Wilderness is a human concept defining amongst other things a world ‘beyond’ our control or even ‘understanding’. It is the bracketing of a physical space in the larger context of a belief in human supremacy. Our lack of engagement with environment is demonstrated by our dependence on being insulated from it.

In home, the artists challenged this statement directly, placing themselves at the ‘mercy’ of the elements whilst undertaking an ten-day walking expedition through the remote and pathless landscapes of the north of Iceland. In consistently misty conditions they had to rely on a mix of basic technology (a 1:100,000 scale map) and increasingly their own instincts to guide them through this rugged terrain. In such an environment, ‘home comforts’ are, indeed, relative – and clearly the most reassuring ‘things’ seen each day were the man-made cairns that continued to guide them ‘home’, and which are the focus of the exquisite photographs in home *.

*Mike Collier in exhibition catalogue Walk On 2013

Exhibition: Slúnkaríki, Ísafjörður, Iceland (1999)

Promised Land took as its starting point the idea of our reliance on fixed and hackneyed symbols and their relationship to the world they are intended to represent. The installation in the Centre for Contemporary Art in Tbilisi combined sculptural, video and printed elements within a single room and by juxtaposing selected symbols and other non-symbolic material elements, the work set out to destabilise their appararent reliability inviting instead, readings of transient and shifting hybridity. A series of wall-mounted prints depicted assemblages of transluscent symbolic forms interspersed with silhouetted found objects. A group of art students from one of the art schools in the City was enlisted to assist in locating local discarded materials, cardboard and furniture in the preparation of the central, sculptural component of the installation. Two video works explored the idea in relation to human expressions of discomfort in respect of unwanted interspecific intruders onto domestic premises and included a text work which, over a period of around 10 minutes by the gradual overlaying of multiple short phrases transformed the screen from black to (almost) white.

Promised Land questions the constitution of the interspecific outsider or ‘other’ within a dominant culture and the bases of acceptance or intolerance. The project considers how ecologies are identified or simply go unnoticed within cultures fixated on individual phenomena and their supposed fixed identity. It considers how the association or juxtaposition of material bodies form new and changing phenomena and meaning, irrespective of human agency or perspective. The project examines the concept of human fear and discomfort in the context of the familiar and how these conditions are manifest in unpredictable and disparate ways. As much as anything, through the deployment of an interspecific lens, the work tests how routine and familiarity, central to our subconscious may be disrupted and threatened sometimes overwhelmingly by marginal and persistent disruption, both actual and imagined.

exhibition: Centre for Contemporary Art, Tbilisi, Georgia