- Museum of Ghost Ruminants

- Museum of Ghost Ruminants

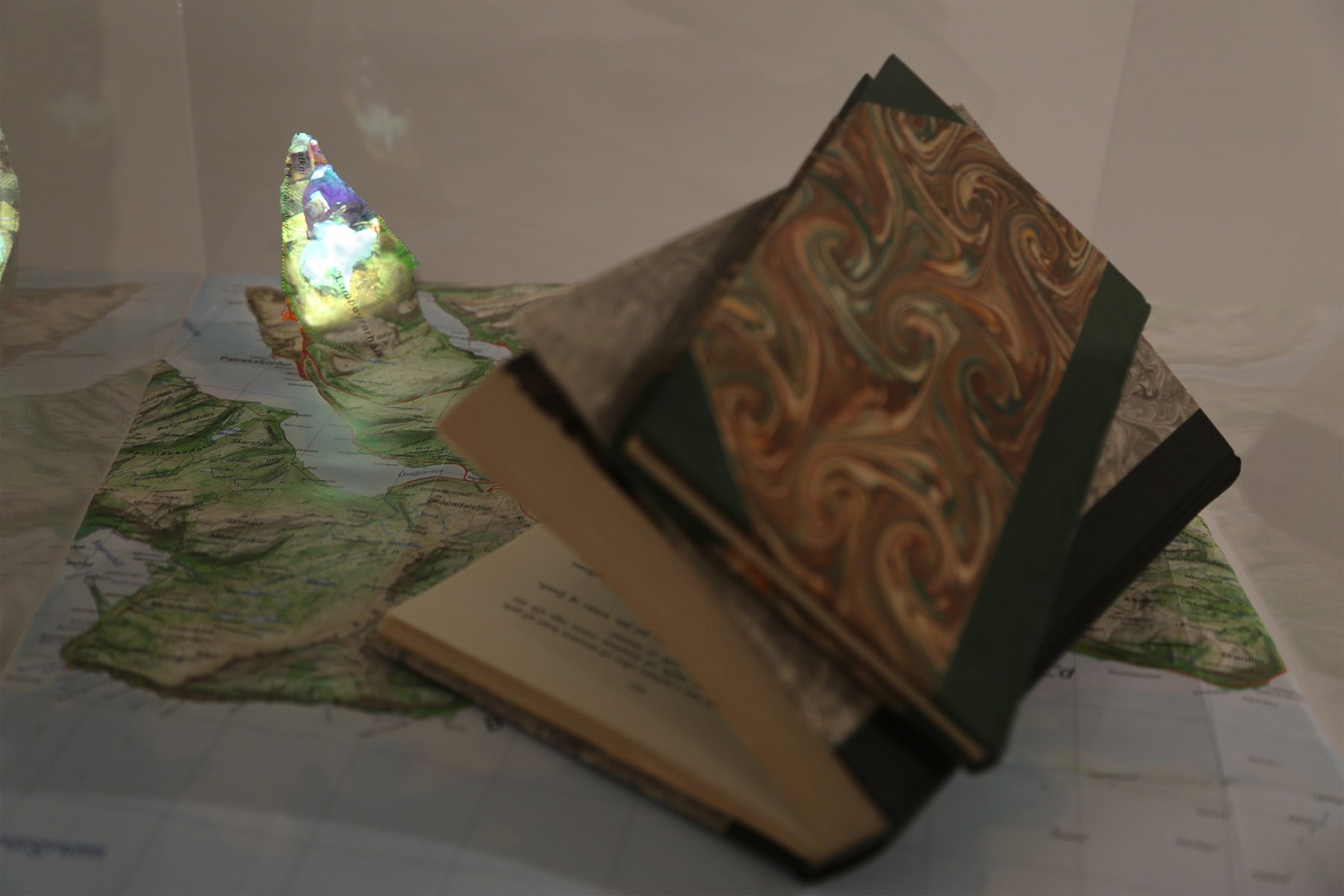

- Tálkni

- shear/sheer

- Gun Bones

- Tálkni peninsula

A project exploring what happens when domestic animals transgress the invisible and unspoken boundaries that separate landscapes of domestication and wildness? In October 2009, a small flock of feral sheep that had persisted for some decades in an inaccessible part of the Westfjords of Iceland was rounded up by a team of men and dogs from the neighbouring communities. Some nineteen sheep were caught, but five more perished as they ran off steep cliffs attempting to evade their captors. Despite (or perhaps because) the incident had caused so much public interest, all those caught were sent to the abattoir the following day. Prior to the round-up, observations were reported suggesting that some physiological adaptations in the sheep were evident. The opportunity to investigate a supposed increase in leg length was lost with the summary disposal of the carcasses.

There is a tension between what we hold culturally as being right and proper and what we observe as a bid by another agent to disrupt that order. At the heart of this case is something that may be dismissed by many to be of no great consequence. For us, in ways resonant with ideas proposed by Jane Bennett (2010) in her seminal book Vibrant Matter, it serves as a vital pointer to expose how human systems suppress the inclinations and capabilities of ‘things’, acknowledging instead only those qualities and capacities we have assigned them.

Human will become blind to the wills of those outside human systems whose actions do not correspond with, or seem at odds with, their own – who are simply not compliant in the human enterprise at hand. When the animal agent is one with which we technically coexist, (a domestic animal) the oversight seems particularly acute. A lack of porosity is evident – a resistance to ideas or indicators of change – a reactionary dismissal of knowledge concerning environment and the adaptability of denizens – the shaping of existence by environment – the capacity of discrete environments to model not only new biological permutations but to spawn new behavioural possibilities as a consequence of introductions or migration – a failure on the part of humans, still to acknowledge that a condition of ‘becoming’ is actually the norm – in nature, stability and material independence are illusory.