The Seas’ Blue Yonder at Húsavík Whale Museum Oct 24 – Dec 25

The Seas’ Blue Yonder at Húsavík Whale Museum Oct 24 – Dec 25

- Apparition (& Hvalreki)

- Apparition

- Apparition (& Soundings)

- The Right Side (Sightings)

- Volcano II (Sightings)

- Greeny (Sightings)

- Minke Whale (Hvalreki)

- Blue Whale (Hvalreki)

- Fin Whale (Hvalreki)

- Hvalreki

- The Path of the Unseen Whale

- Soundings

- Seas’ Blue Yonder/Skaftfell

- exhibition poster image

- Apparition

- Apparition

- Gallery talk

- Apparition

The Seas’ Blue Yonder – Sjávarblámi exhibition is the culmination of over two years of development by Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir & Mark Wilson, and was curated by Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir. This show delves into the intricate relationships between humans and whales, exploring the dichotomy between what we perceive of them above the sea’s surface and the significance and complexity of whale species within the marine ecosystem.

The exhibition is anchored in the history of the whaling station at Vestdalseyri near Seyðisfjörður. In the mid to late 1800s, this site was home to one of the world’s first industrial whaling stations, established by the pioneering American whaler and inventor, Thomas Welcome Roys. This historical context serves as a poignant backdrop, framing the contemporary discourse on human-whale relations.

In the exhibition, The Seas’ Blue Yonder, for iconography we focused on what whales present of themselves, beyond the sub-aquatic environment – what of whales is visible above the seas’ surface, either in part, as living beings, or in their entirety, as stranded bodies, dead or dying.

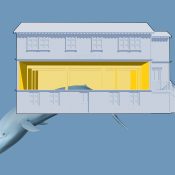

The sculpture Apparition is of a whaleback – specifically modelled on the back of a particular blue whale, a regular visitor to Skalfandi Bay and known by Whale Research Centre scientists as The Right Side. The artwork is divided into nine sections – the first four sections from the rear being closely juxtaposed, and so carrying the continuity of the whale’s form. From the fifth to the front, the sections begin to drift and misalign, thereby disrupting and distributing that form, lengthways and to a degree, laterally.

The human relationship to whales is complex, both currently and historically, encompassing every regard and disregard for their being, from admiration, respect and wonder, to objectification and industrial-scale exploitation. Most recently the whale has been recognised as being of great marine ecological significance, both in life and in death – live whales being huge capturers of carbon, nourishing the shallower and mid-level ocean with their waste and in death, the ‘whalefall’ of deceased cetaceans being hugely instrumental in feeding and replenishing deep sea ecosystems. Apparition’s segmentation and conspicuous fragmentation – first seeming to hold and then relinquishing its combined form – reflects this complexity of approaches and ultimately echoes what cetacean scientists are the first to reflect, that there is so much about all species of whale, their behaviours, their idiosyncratic sentient capacities and nature, their communicative powers and so on, that remains far beyond our comprehension. The colour of the work (or apparent lack thereof), acknowledges that Apparition provides a surface upon which all manner of views will inevitably be projected.

Hvalreki (Windfall) too, is a multiply-constituted work. Comprising (in Skaftfell) 21 x ink drawings on paper, the series of framed works is scattered randomly across a long wall. Their distributed arrangement is suggestive of the apparent randomness and certainly, unpredictability in their strandings both in time and geographical location. One Icelandic whale, (a minke) is set apart on an adjacent wall. Although some casualties are identifiable as ship strikes, which kill, maim or fatally disorientate, so many more beachings each year, on shores around the world, happen with no clear cause, leaving countless individuals and pods inexplicably helpless, dead or doomed.

Historically in Iceland, when such events occurred, the arrival of a whale in this way was seen as a windfall and a great cause for celebration. Local communities would gather on the sands to harvest its prodigious flesh, blubber and oil, to keep them in food and provisions for months. The traditional Icelandic term gives an ironic title to the work, since in our times, in most cases the whale’s corpse’ unexpected appearance is first met with a sense of tragedy and pathos, followed by vexation as municipalities shoulder the task and expense of cutting up and burying the enormous bodies.

Soundings is a trio of videos which again digs into something of the multiple ways we regard the whale – the first screen shows a series of short clips of blue whales, filmed by a cetacean biologist using drone cameras around the mouth of Skalfandi Bay. Scientists work each year, all season from late spring to early autumn at the Research Centre there in Húsavík gathering and analysing data on blue as well as humpback, minke whales and dolphins.

The second screen shows an underwater camera deployed in Seydisfjördur around the site of Vestdalseyri where in the mid to late 1800s, one of the world’s first industrial whaling stations was set up by an American whaler and inventor, Thomas Welcome Roys. His pioneering work with the rocket harpoon and whale-raising technology, together with the development of faster steamships meant that for the first time, it was possible not only to catch and kill the greatest and fastest species, notably the fin and blue whales, but also to prevent them from sinking irretrievably and being lost. Ragnar Edvardsson (a marine archaeologist working out of the Westfjords), having discovered blue whale bones in the sea around other, later whale stations in Iceland is convinced that they are still there to be found around Vestdalseyri.

The third video (entitled Childhood Memories from a Whaling Station sees Marsibil Sól Þórarinsdóttir Blöndal reminiscing on her annual summer experiences as a child at the whaling station at Hvalfjördur in attendance with her father (a seasoned whale flenser) and her vegetarian, activist mother – and grappling with some of the arising contradictions regarding her memories of profound happiness there, coupled with the more visceral recollections and her perspectives now as a young, vegan adult.

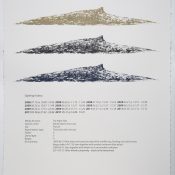

Sightings is a series of three screenprints each dedicated to an individual blue whale which along with many others, is the subject of scientific study by researchers working out of Skalfandi Bay. The whales, identified as Greeny, The Right Side and Volcano II when they surface, are recognizable by the unique pigmentation pattern they carry on their skin and in each case, it is this pattern, distinct from the form itself, which we used to create the whaleback images. The whales are seen returning to the Bay year on year and each sighting is recorded together with notes concerning some behaviours and sometimes, with whom the whale was accompanied at that time.

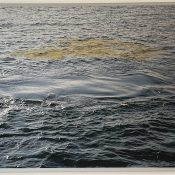

The Path of the Unseen Whale is a mixed media piece which incorporates a photographic image of a whale fluke print overlaid with glass, on the underside of which, the unique markings of the blue whale Volcano II have been printed in gold ink. The fluke print itself is a mark temporarily left on the surface of the waves by the tail fluke when a whale dives – it is caused by the creation of a vortex in the water together, it is thought, with some shedding of surface oil from the whale’s skin. The title comes from a translation of the Iñupiaq term for fluke print, ‘qala’.