Lee on human-pigeon co-habitation in a Shoreditch studio

All posts by Mark Wilson

Hunter Gatherer – PSL (Project Space Leeds), UK. 2011

Nine artists from across the North of England were invited to create new work in response to Artemis, an amazing collection of over 10,000 objects relating to world cultures, fine and applied art, science, natural history, textiles and costume, social history, childhood and more. Based in Holbeck, Leeds, the collection forms an art loan service for Education Leeds to which artists have been given exclusive access. The title of the show ‘Hunter Gatherer’ refers to a term used by anthropologists to describe the way in which human beings collected food before the advent of agriculture. Here it references the artists and the processes they employed in sifting through the vast Artemis collection. The resulting works include sculpture, installation, film, prints and drawing which form part static exhibition and part on-going project within the space. Curated by Pippa Hale.

For some time we have been working with ideas of representation and the shortcomings that any representation must acknowledge and bear. With representation comes the responsibility for the abbreviations it makes of the thing represented. When we found the decoys, boxed up in amongst the shelving we liked the rather sad sense of expiration they seemed to exude. Whatever they were made for, it seems their useful life was over – and yet they were eloquent in their rather perished and redundant condition. There is humour here, even absurdity – decoys (a bit) like this were and are used for attracting live, inquisitive pigeons in order that they be shot as vermin or to fill the pastry shells of latter day hunters. Yet now they look so forlorn and somehow unlikely, it seems hard to imagine that they ever constituted a lure of any kind for real, living birds.

Birds, like humans, mistake simulacra for the real thing at their peril. We live in a constructed world populated by representations that suit us and make of the real world something manageable and tolerable. Such illusions make us vulnerable.

During a recent project we gathered anecdotes from people regarding human- non-human animal encounters. The tale told here concerns the alliance between an artist living and working in a huge warehouse space in East London and a resident flock of some 200 pigeons, upon whose presence his work and living arrangements are ultimately absolutely dependent.

The spikes are designed to deter birdlife and most commonly, pigeons. Between the lure and the deterrent we position ourselves – because of the very specific nature of these items of equipment, their duplicity and contradictions, it’s clear that we have designs on pigeons – and yet despite our apparent antagonism the dove (note the euphemism) is our ultimate symbol of peace and biblically, the perennial symbol of hope.

(The title is lifted from Stan Bonnar’s excellent essay LOST: Context Provocation Mythogram published 1999 in Decadent by Foulis Press)

White Noise

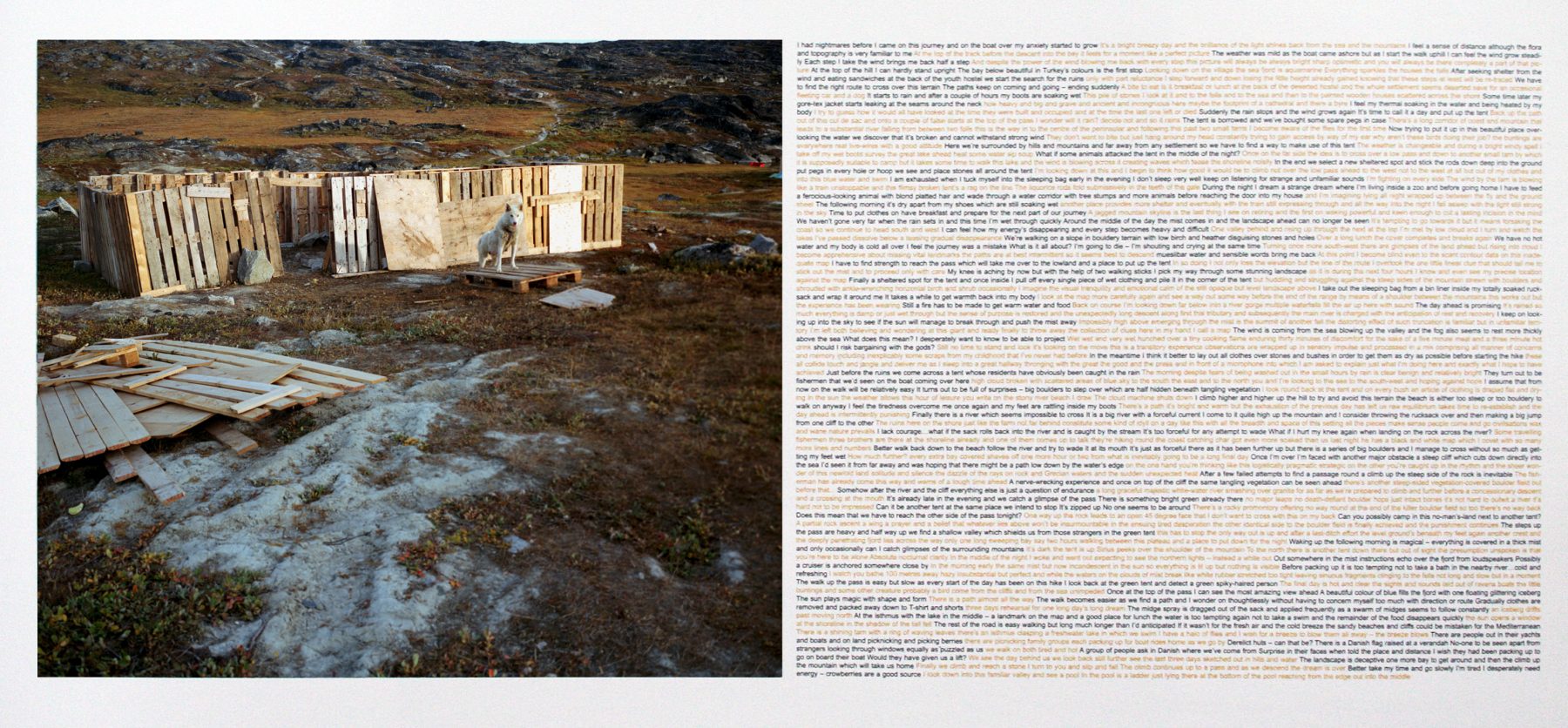

White Noise comprises a text – a duel and dovetailed account of a journey by foot through unfamiliar, difficult and possibly dangerous territory together with the image of a Greenlandic sled dog standing guard outside an ad hoc shelter of wooden palettes.

The two of us had walked together in Greenland through uninhabited and difficult terrain for five days. On our return we each wrote an account of the experience including specific responses to events on the journey including thoughts, anxieties, expressions of wonder and even dreams, sequenced in the order by which they occurred. Both narratives begin and end with descriptions of the walk itself but with the serial cut-and-paste delivery of short phrases from each protagonist in turn, the narrative sequence is disrupted as things are remembered differently and with different emphasis. As a consequence, similar experiences reappear almost as memories, haunting the narrative of the other.

During the same period we’d travelled further north and it was in Ilulissat, well into the Arctic, that we’d become fascinated with the colonies of sled dogs occupying parts of the town and its surroundings. In Ilulissat at that time, the dogs outnumbered the human population of 4000 by half as much again. What fascinated us and in some senses set off our long term interests in human/animal relationships was the distinctive and liminal place these animals held in a (simplified) spectrum ranging (in decreasing proximity to the human) from pets (companion species) through working animals, to livestock, game, feral and finally beyond to wild animals.

Simplified or not, there in the north, what we were told and indeed what we observed, was that in relation to the Greenlandic sled dog, the term ‘pet potential’ is an oxymoron. They have been bred to work for humans whilst still maintaining a highly developed sense of pack hierarchy. Historically, (unsubstantiated) stories abound of the regular replenishing of strength and wildness in the stock by staking females in heat out in areas where there are wolves. In this subject we were drawn to the embodiment of conflated domesticity (familiarity) and wildness (uncertainty) which remained resistant to both classifications.

To read the text work, open the PDF here

nanoq photographic archive at selected locations

- Askja House of Natural Sciences, University of Iceland

- Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, UK

- Oxford Museum of Natural History, UK

- Fram Museum, Oslo, Norway

- North Atlantic House, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Leicester Museum and Art Galleries

- Grenna Museum, Sweden

- Nordic House, Faroe Islands

Fox Reports

The Fox Reports from Bryndis Snaebjornsdottir on Vimeo.

Though we may start by looking at something, we soon have to realize that we are looking for something – that we are in fact searching for a way of experiencing that which is presented to us.

Paradoxically, we tend to allow those things that are most familiar to remain outside of us, precisely because we know them so well that we need no reassurance of their identity. Its when regarding things that are unfamiliar that we need to find the inner resources that might allow us to make some sense of them we construct metaphors to describe something for which we have no words. Often these metaphors are adopted into our language, and we forget that they’re metaphors.

Artists have a difficult time in relation to the metaphorical. We attempt to find or construct metaphors, because we want to refer to things without naming them. But as soon as we do find them we resent their efficacy, because once the metaphor has been found the object loses its mystery and ceases to be worth searching for.

Artists often talk about the search in terms of the process its the process thats important, the object is simply that, an object that has resulted from the process of the work. But how can one genuinely search without trying to find, or engage in a process without hoping for a result? One might borrow the strategies of the anthropologist: keeping ones distance; shrouding the discovery. Or one might try to maintain the innocence necessary to stay within the present tense; to remain within the voice of the present tense focused in the moment and not on the object.

What is sought may not be the material object of the search, the unfamiliar object, but the internal space that is accessed through the act of searching and the engagement with the unknown. In The Space of Literature Maurice Blanchot talks of [making] of the work a road toward inspiration and not of inspiration a road toward the work. We are advised then not to seek in order to find, but to use the possibility of finding, even the inevitability of finding, as an impetus towards searching.

Essay for lullabies catalogue by Professor Juan Cruz, Royal College of Art, London

Exhibited: Reykjavík Art Museum (2003)

Interview Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson

An interview with the Artists by Georgian TV on site during the installation of Promised Land

hornstrandir

5th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art – State Darwin Museum

British Russia Year of Culture 2014 @ State Darwin Museum, Moscow

Vanishing Point was shown in 2014 on a vast exterior wall at the State Darwin Museum in the Russian capital. For the first three weeks in February, the video was screened each evening between 6.30 and 11.00 pm and was seen as something of an antidote to the long winter nights in Moscow.

The Darwin Museum’s publicity for the screening explained: “This gift is not only for visitors, but for those who are waiting at the bus stop or passers-by. No matter how fast you race past, there’s time enough for it to catch the eye. Blue sky, wind, unity and harmony between man and nature – something sorely lacking in the big cities.”