(a)fly extends the artists cycle of projects examining human relationships to landscape and environment by way of observing the human/animal interface. In this instance they concentrated on domestic animals within an urban environment. The title (originally a fly in my soup), makes reference to an often awkward and sometimes problematic collision between culture and nature. By taking the city and even the domestic environment as the coalface of this exchange it staked out new ground for a reappraisal of the way we relate to the wider environment as revealed through this particular set of relationships.

The basic structure of the project is a survey, mapping pets in the inner city area of Reykjavik. Four ptarmigan hunters turned their guns on maps, at a distance of 50 metres thereby selecting specific residential properties within Reykjavík 101. The owners were contacted and from this process, pet owners in the area were identified.

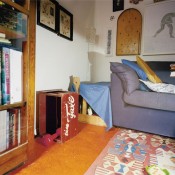

A key component of the project is a series of photographs taken of the environments (homes) of pets either constructed by owners or chosen by pets themselves within the environs of their hosts.

Our research found many restrictions and regulations related to the keeping of animals and pets in Reykjavík, some of which are very different from other cities that we know in the U.K. or USA. In Reykjavík at that time, dogs were technically forbidden by law. You can apply for a license (that costs approximately 15,000 ISK or £200). With the license come obligations to micro-chip your dog, and show proof that it is wormed and vaccinated by a vet on a regular basis. Around this time a similar law was passed by the City Council in Reykjavík regarding the keeping of cats.

Professor Ron Broglio, Department of English at ASU wrote the following about the project.”…This same absence of the animal world is evident in the current project a fly in my soup as in other projects by Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson. In (a)fly [the artists] travelled to Iceland and photographed the space in peoples’ homes where their animals dwell. It may be a dog bed, a cat corner, a fish bowl, etc. The photographs do not include the animal – only their setting. As with nanoq, the absence of the animal haunts their work. In this case, viewers must negotiate the (often oedipalized) human expectations of a pet with the question of what the animal perceives. There is an uncomfortable fit between the animal’s residual space in the human’s habitat and the photograph which makes the animal’s place central. [They do not] photograph the well-kept family room or the front façade of the house; rather, they photograph corners and washrooms, stairs and ledges. Wilson and Snæbjörnsdóttir force the question, “From whose umwelt are we seeing this place?” No longer are we opening the animal up in order to name and know it. Rather, knowledge comes from the displacement of perspective and from the uncomfortable haunting provided by the surface of another world that lingers as a remainder in our own.”

Exhibited: National Museum of Iceland and Reykjavík City Library as part of Reykjavík International Art Festival in 2006. Also in Gothenborg Konstmuseum , Sweden (2007)