(a)fly extends the artists cycle of projects examining human relationships to landscape and environment by way of observing the human/animal interface. In this instance they concentrated on domestic animals within an urban environment. The title (originally a fly in my soup), makes reference to an often awkward and sometimes problematic collision between culture and nature. By taking the city and even the domestic environment as the coalface of this exchange it staked out new ground for a reappraisal of the way we relate to the wider environment as revealed through this particular set of relationships.

The basic structure of the project is a survey, mapping pets in the inner city area of Reykjavik. Four ptarmigan hunters turned their guns on maps, at a distance of 50 metres thereby selecting specific residential properties within Reykjavík 101. The owners were contacted and from this process, pet owners in the area were identified.

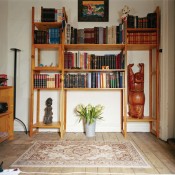

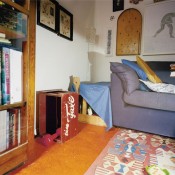

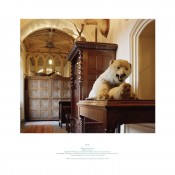

A key component of the project is a series of photographs taken of the environments (homes) of pets either constructed by owners or chosen by pets themselves within the environs of their hosts.

Our research found many restrictions and regulations related to the keeping of animals and pets in Reykjavík, some of which are very different from other cities that we know in the U.K. or USA. In Reykjavík at that time, dogs were technically forbidden by law. You can apply for a license (that costs approximately 15,000 ISK or £200). With the license come obligations to micro-chip your dog, and show proof that it is wormed and vaccinated by a vet on a regular basis. Around this time a similar law was passed by the City Council in Reykjavík regarding the keeping of cats.

Professor Ron Broglio, Department of English at ASU wrote the following about the project.”…This same absence of the animal world is evident in the current project a fly in my soup as in other projects by Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson. In (a)fly [the artists] travelled to Iceland and photographed the space in peoples’ homes where their animals dwell. It may be a dog bed, a cat corner, a fish bowl, etc. The photographs do not include the animal – only their setting. As with nanoq, the absence of the animal haunts their work. In this case, viewers must negotiate the (often oedipalized) human expectations of a pet with the question of what the animal perceives. There is an uncomfortable fit between the animal’s residual space in the human’s habitat and the photograph which makes the animal’s place central. [They do not] photograph the well-kept family room or the front façade of the house; rather, they photograph corners and washrooms, stairs and ledges. Wilson and Snæbjörnsdóttir force the question, “From whose umwelt are we seeing this place?” No longer are we opening the animal up in order to name and know it. Rather, knowledge comes from the displacement of perspective and from the uncomfortable haunting provided by the surface of another world that lingers as a remainder in our own.”

Exhibited: National Museum of Iceland and Reykjavík City Library as part of Reykjavík International Art Festival in 2006. Also in Gothenborg Konstmuseum , Sweden (2007)

dwellings

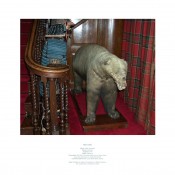

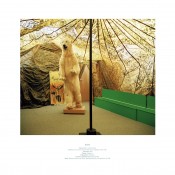

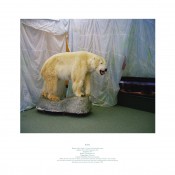

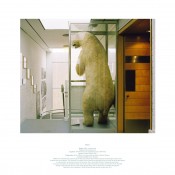

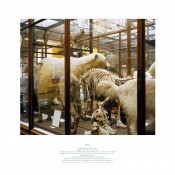

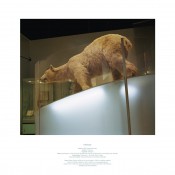

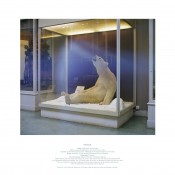

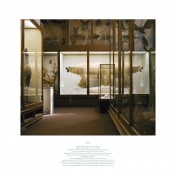

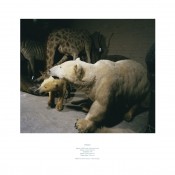

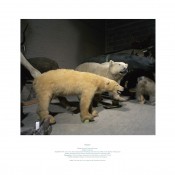

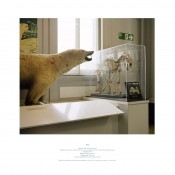

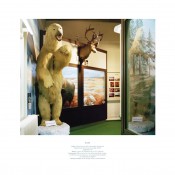

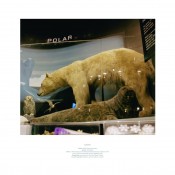

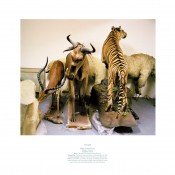

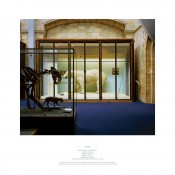

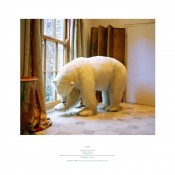

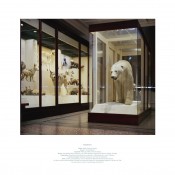

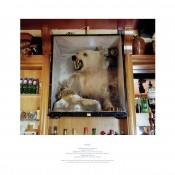

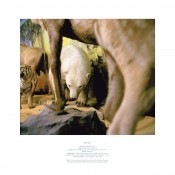

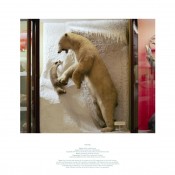

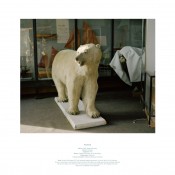

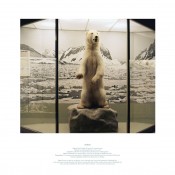

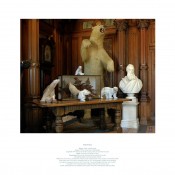

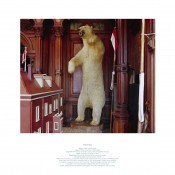

photographic archive from the artists survey of taxidermic polar bears in the UK

- Belfast

- Blair-Atholl

- Bristol (Misha)

- Bristol (Nina)

- Dover

- Dublin

- Edinburgh

- Edinburgh

- Exeter

- Fyvie

- Glasgow

- Glasgow

- Halifax

- Hull

- Kendal

- Leeds

- Leicester

- Liverpool

- London

- London

- Manchester

- Masham

- Newcastle

- Norwich

- Somerset

- Worcester

- Peterhead

- Rawtenstall

- Sheffield

- Somerleyton

- Somerleyton

- Sunderland

- Tring

nanoq photographic archive at selected locations

- Askja House of Natural Sciences, University of Iceland

- Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, UK

- Oxford Museum of Natural History, UK

- Fram Museum, Oslo, Norway

- North Atlantic House, Copenhagen, Denmark

- Leicester Museum and Art Galleries

- Grenna Museum, Sweden

- Nordic House, Faroe Islands

Fox Reports

The Fox Reports from Bryndis Snaebjornsdottir on Vimeo.

nightwatch

nightwatch from Bryndis Snaebjornsdottir on Vimeo.

Though we may start by looking at something, we soon have to realize that we are looking for something – that we are in fact searching for a way of experiencing that which is presented to us.

Paradoxically, we tend to allow those things that are most familiar to remain outside of us, precisely because we know them so well that we need no reassurance of their identity. Its when regarding things that are unfamiliar that we need to find the inner resources that might allow us to make some sense of them we construct metaphors to describe something for which we have no words. Often these metaphors are adopted into our language, and we forget that they’re metaphors.

Artists have a difficult time in relation to the metaphorical. We attempt to find or construct metaphors, because we want to refer to things without naming them. But as soon as we do find them we resent their efficacy, because once the metaphor has been found the object loses its mystery and ceases to be worth searching for.

Artists often talk about the search in terms of the process its the process thats important, the object is simply that, an object that has resulted from the process of the work. But how can one genuinely search without trying to find, or engage in a process without hoping for a result? One might borrow the strategies of the anthropologist: keeping ones distance; shrouding the discovery. Or one might try to maintain the innocence necessary to stay within the present tense; to remain within the voice of the present tense focused in the moment and not on the object.

What is sought may not be the material object of the search, the unfamiliar object, but the internal space that is accessed through the act of searching and the engagement with the unknown. In The Space of Literature Maurice Blanchot talks of [making] of the work a road toward inspiration and not of inspiration a road toward the work. We are advised then not to seek in order to find, but to use the possibility of finding, even the inevitability of finding, as an impetus towards searching.

Essay for lullabies catalogue by Professor Juan Cruz, Royal College of Art, London

Exhibited: Reykjavík Art Museum (2003)

Interview Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson

An interview with the Artists by Georgian TV on site during the installation of Promised Land