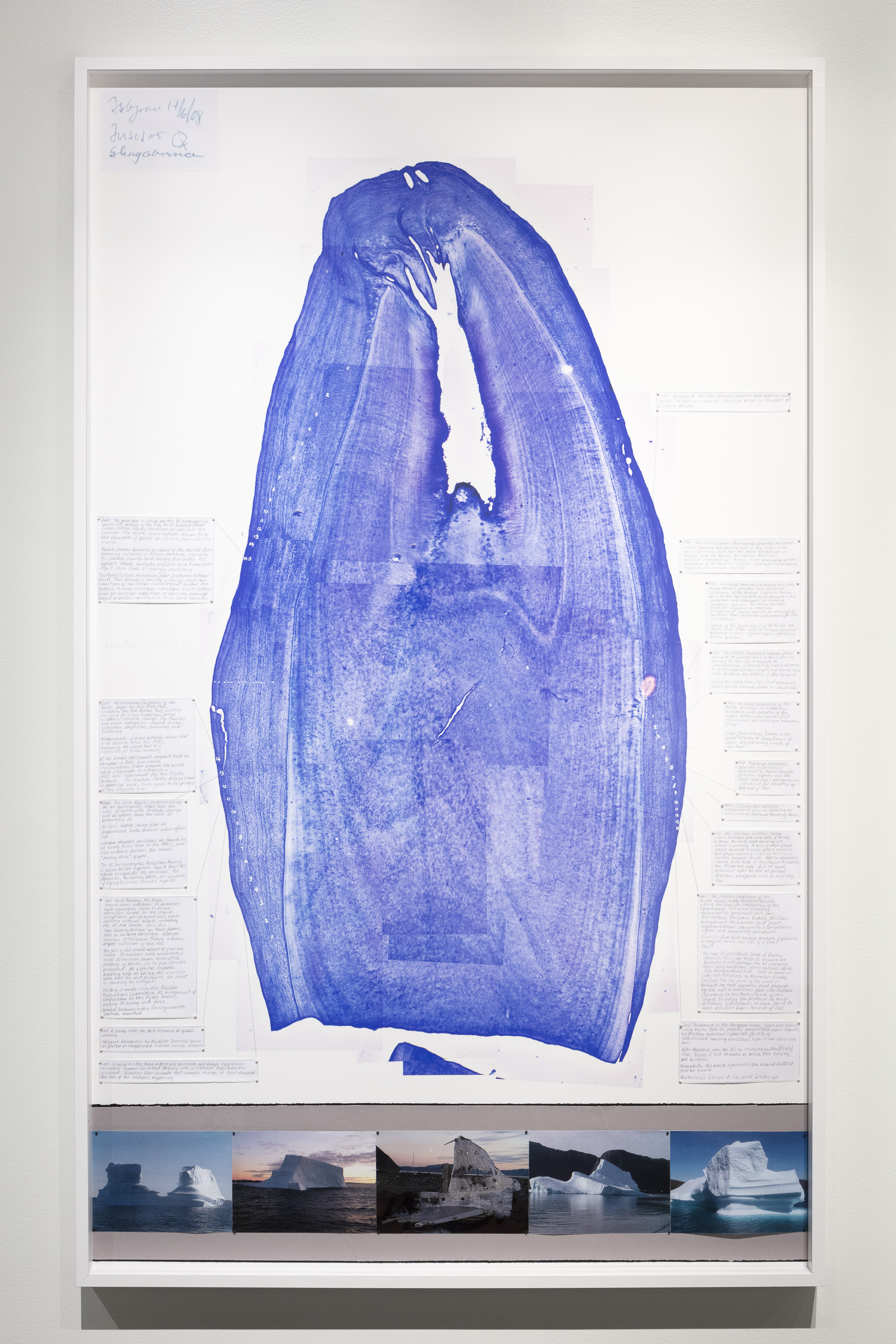

Elevation #6: the ebbing

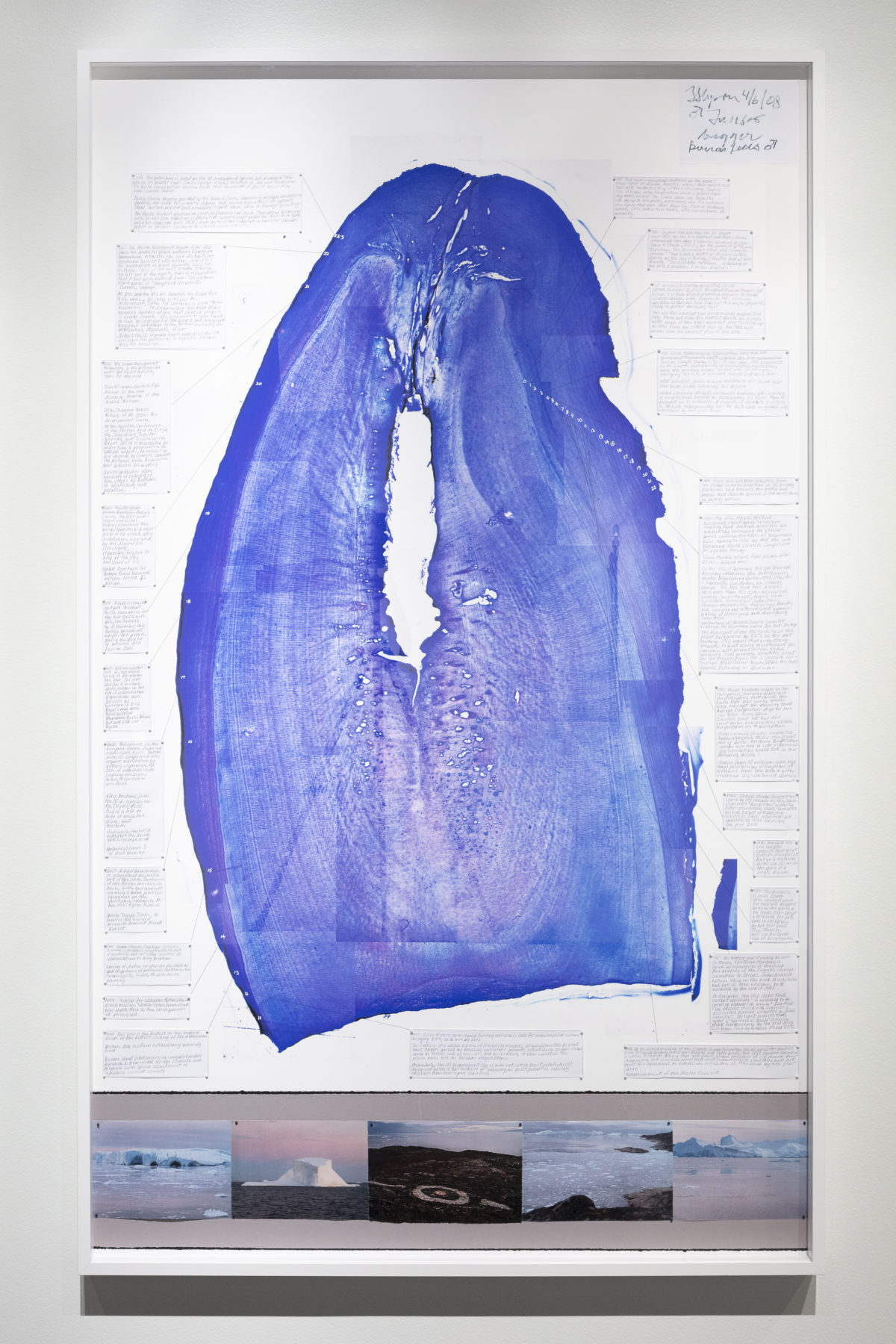

Elevation #4: flood/wave/flood (detail) ceramic tiles on pallets

Elevation #4: flood/wave/flood (detail) ceramic tiles on pallets

The Only Show in Town

an introduction by Jo-Ann Conklin, Director of the Bell Gallery

It’s 4:30 am on a late-June morning when I arrive to pick up BryndísSnæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson from their bed and breakfast in Providence. We are on our way south, to Jacob’s Point, a marsh in Warren, RI, where Deirdre Robinson and Steve Reinert are researching saltmarsh sparrows. As we arrive, it is already warm – the sun is rising on the marsh, glistening in dew on the grasses; it is peaceful and beautiful, and awe inspiring. The crew is already set up, going about their business of looking for saltmarsh sparrow nests: small indentations in knee-high grasses that are invisible to the untrained eye. Their task is to band the birds and to record their nesting habits, their successes and unfortunate and increasing failures in the face of incrementally rising sea levels.

Elevation #1: escape/release 3

Experiences such as this are commonplace for Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson, whose research-based art practice has led them to collaborate with specialists in far-flung natural settings around the globe.[1]Over their twenty-year collaboration, they have created artworks addressing California condors and humpback chub in Arizona’s Grand Canyon, polar bears living in Alaska and taxidermied in the UK, seals in Iceland, gulls in Sweden – and even our pets. In each of these series, they examine the “cultural lives” of animals — the relationship between non-human and human animals and how human culture intersects with, and often interrupts, the balance of nature. Their works intersect with issues in animal studies, as well as broader studies of colonialism, ecology and climate change.

Which brings us to the saltmarsh sparrow. What story do Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson have to tell us about the saltmarsh sparrow, and what story do the sparrows have to tell about us? Living exclusively in narrow and depleted marshlands along the eastern coast of the US, saltmarsh sparrows are threatened by landfilling for development on one side and sea-level rise on the other. Rhode Island’s saltmarshes are among the most vulnerable in the United States because of their low elevation and because the rate of sea-level rise in the Northeast is higher than in other places.[2]

Saltmarsh sparrows are among a number of species that breed in this delicate and endangered landscape. Nesting on the ground, saltmarsh sparrows—Ammospiza caudacuta—have evolved a highly particularized breeding habit that allows them to mate, lay, hatch, and fledge chicks within twenty-eight-day cycles – the time between high tides when the marshes flood. The female lays her first egg five days after mating, then lays one each day for two or three days (the chicks may be the offspring of several males, who have no responsibility for rearing chicks). Incubation takes about twelve days, and it takes seven to eight days for the chick to be strong enough to climb out of the nest (they cannot fly or swim). If not perfectly performed—if the female has mated late or built her nest too close to the water’s edge—when the water rises eggs float out of the nest and are lost, or chicks that are too young to climb up the marsh grasses die of exposure or are drowned. Sea-level rise from climate change has shifted this delicate balance. Saltmarsh sparrow populations have decreased by 75% since 1998, and at some point in the next fifty years the sparrows will cease to exist.[3]Although there are aspirations for floating saltmarshes and other extraordinary measures, the impending loss of the species is accepted fact among the orthnithological community. It was this assertion, made by ornithologist Charles Clarkson during an early interview for the artists’ project at Brown, that stunned Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson and catalyzed their exploration into the plight of the saltmarsh sparrow.

Avian researchers—like Robinson and Reinert, and Chris Elphick, principal investigator of SHARP, the Saltmarsh Habitation and Avian and Research Program—are racing the clock and the tides to learn as much as possible about saltmarsh sparrows prior to their extinction, and to build support in hope of saving other saltmarsh species. In spring of 2017, biologists Robinson and Reinert initiated their citizen science project, the Saltmarsh Sparrow Research Initiative (SALSri). The impetus was a serendipitous sighting of a banded saltmarsh sparrow at Jacob’s Point, made by Robinson the previous summer. Finding a banded bird is unusual. Curious to know more, Robinson elicited the help of Reinert, a Master Bander. They captured and identified the bird. Referencing the band codes, they learned that she had been banded in Florida on October 31st, 2015. This tiny bird, weighing only 0.7 oz., had migrated 1,243 miles from Florida to Rhode Island — setting the record for the longest documented migration for her species.

Elevation #1: escape/release 4

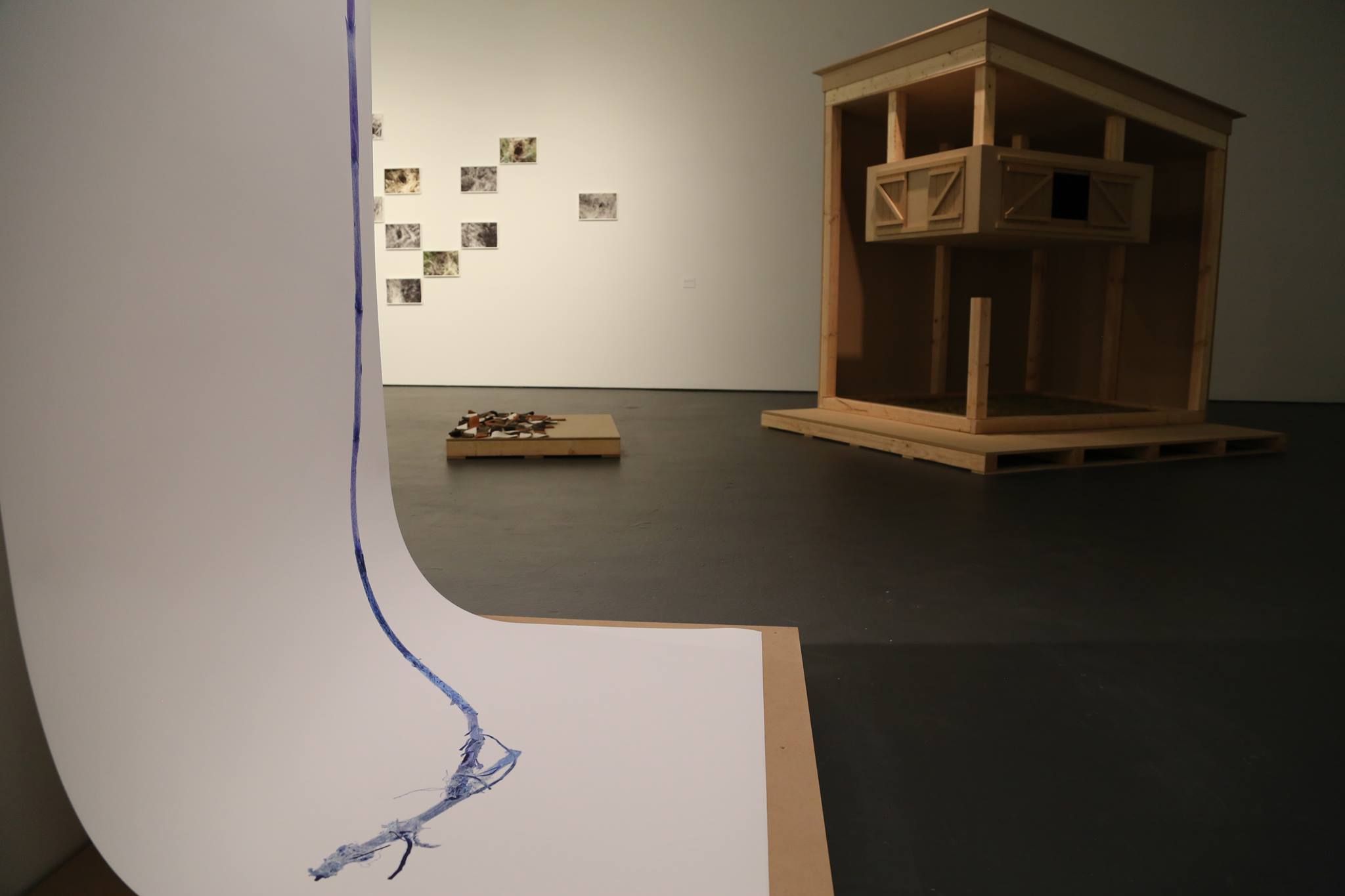

Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson’s research-based artworks are multidisciplinary in nature, most often taking the form of installations, involving diverse media including sculpture, found objects and materials, video, audio, drawing, photography and texts. In The Only Show in Town,as in their other projects, they “represent the process of research itself.”[4]Through a series of six works in the exhibition, the artists invite us to join them in the saltmarsh, to share their experience, which Mark describes as “the significant search for some understanding not yet known.”[5]

As they entered the saltmarsh on that June morning, the artist team was instructed in the first rule of the marsh: the need to walk slowly and deliberately in order to study the ground beneath their feet, “to distinguish between promising-looking twists of dried grass and the constructions that would hold or had once held the eggs and hatchlings of saltmarsh sparrows.”[6]Robinson pointed out nests and gave instructions on how to find them — Mark was a natural, identifying a nest almost immediately. In the exhibition, this search is translated into an arrangement (a field or marsh) of photographs. Viewing the photos, which are shot down on tangles of grasses, we join in the search for nests, looking beyond the surface texture to find the tell-tale indentation of the nests.

Elevation #1: escape/release 2

Elevation #1: escape/release 2

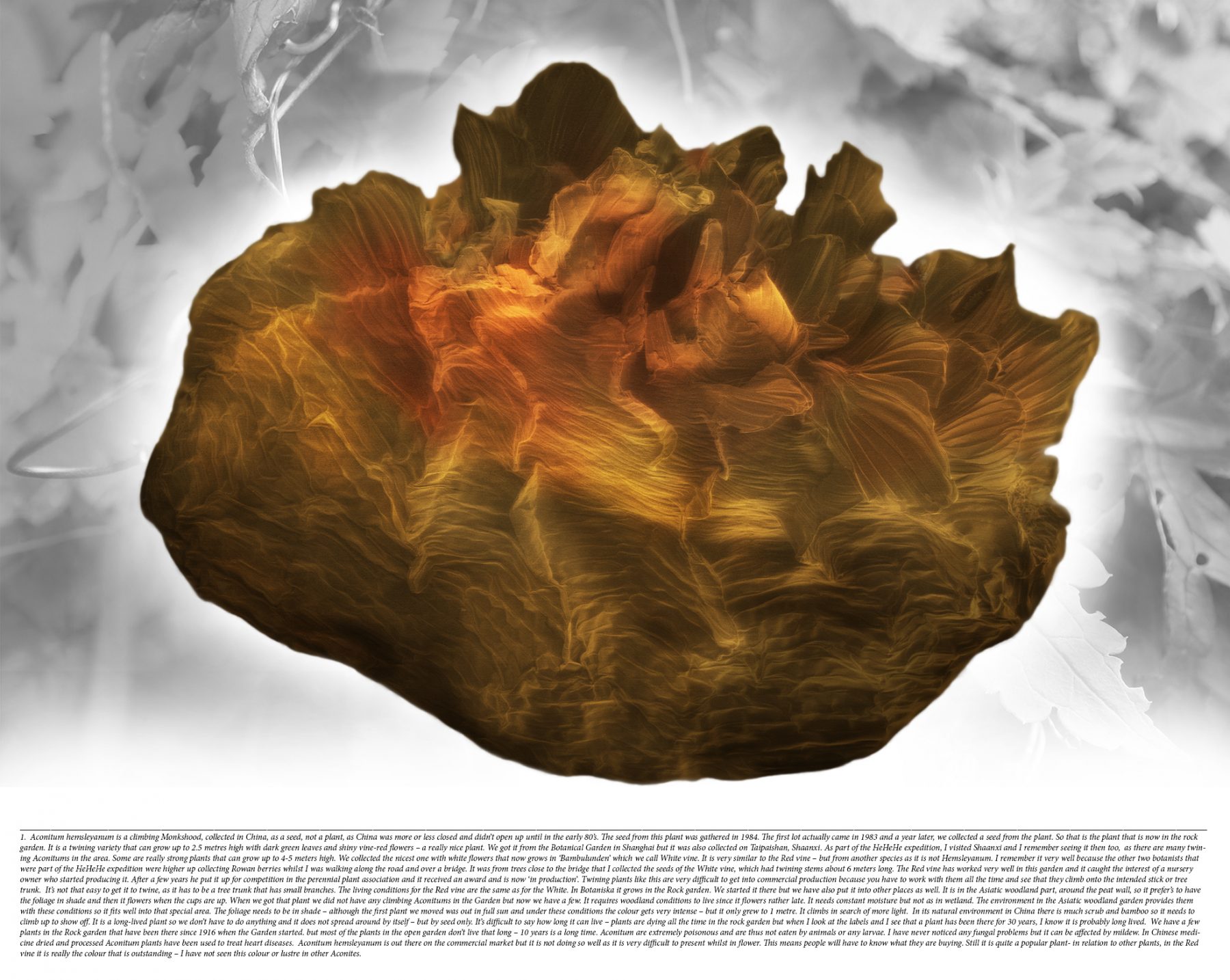

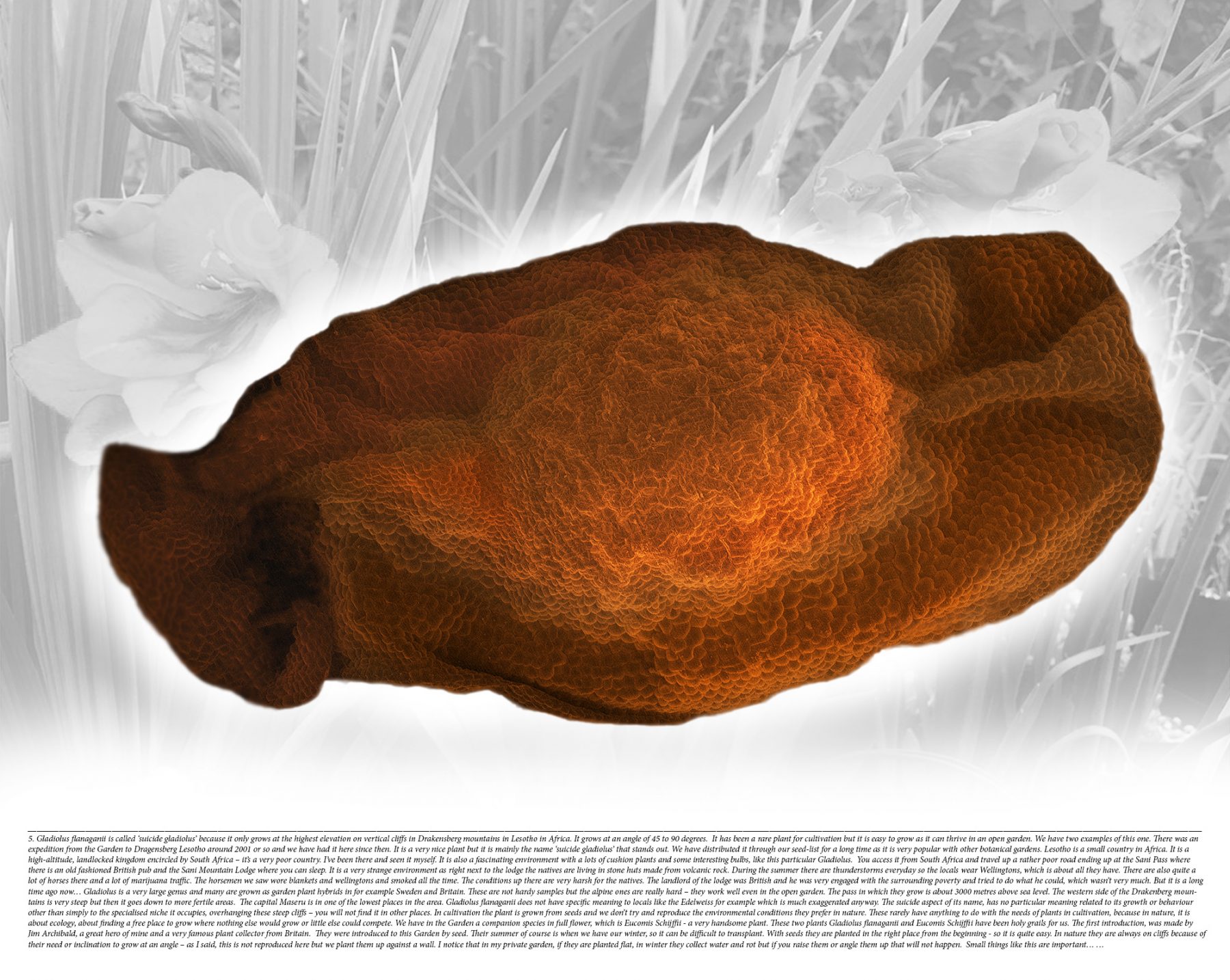

While Mark sought out nests, Reinert instructed Bryndís in the identification and properties of cordgrass, salt hay grass, and glasswort—plants common to the marsh. The work entitled Salicornia depressais their 172” high photograph of one such plant, commonly known as glasswort or pickleweed. A fleshy, salt-tolerant plant, glasswort is usually the first plant to grow in high-salt environments, making it invaluable in the establishment of new marshes. Additionally, it provides a habitat for invertebrates, is a food source for many animals, and is edible to humans.

Working with student technicians and a photomacrographic system at the RISD Nature Lab, Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson scanned a sample of the grass in sections, each section stack-scanned 65 times, and later reassembled these, in Photoshop, to produce this highly detailed image. The extreme magnification of the image invites us to look closely, to examine the plant in a way not possible with the human eye, and to enable a scale-shift more correspondent with the view of a creature the size of a sparrow.

Salicornia depressareflects the artists’ concerns with plant blindness. Identified by biologists James H. Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler in the late 1990s, plant blindness refers to the human tendency to ignore plant species and to disregard their importance.

We defined plant blindness as: the inability to see or notice the plants in one’s own environment—leading to: (a) the inability to recognize the importance of plants in the biosphere, and in human affairs; (b) the inability to appreciate the aesthetic and unique biological features of the lifeforms belonging to the Plant Kingdom; and(c) the misguided, anthropocentric ranking of plants as inferiorimals, leading to the erroneous conclusion that they are unworthy of human consideration.[7]

Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson contend that, “In view of increasing species extinction, the world can no longer afford our citizens to see ´nothing´ when they look at plants, the basis of most life on earth.”[8]In a symbolic act of respect the artists returned the specimen of glasswort to Jacob’s Point and replanted it.

Elevation #1: escape/release 1

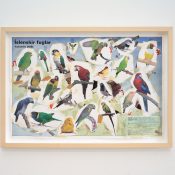

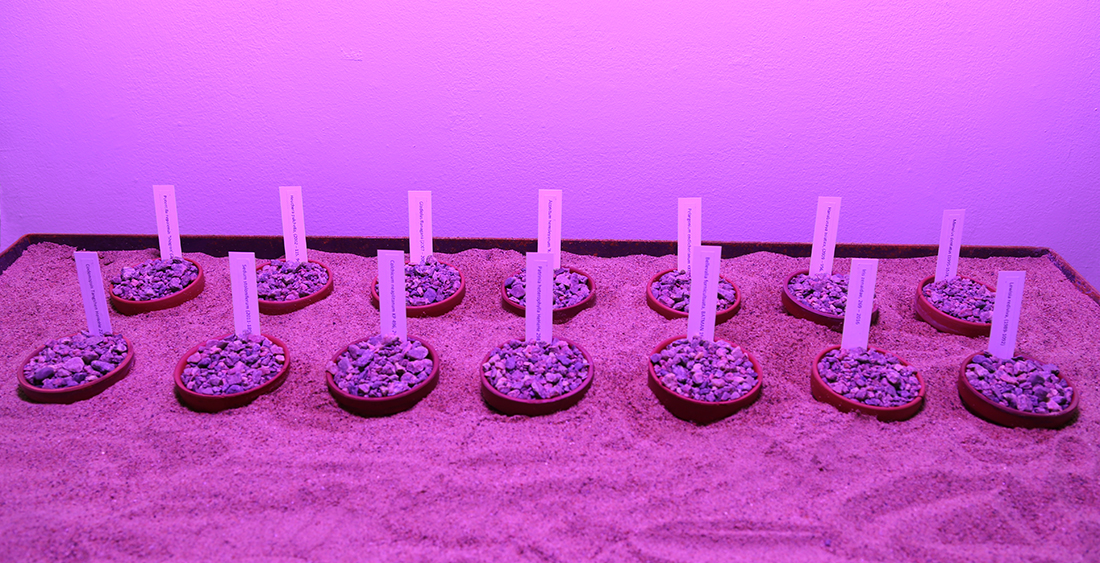

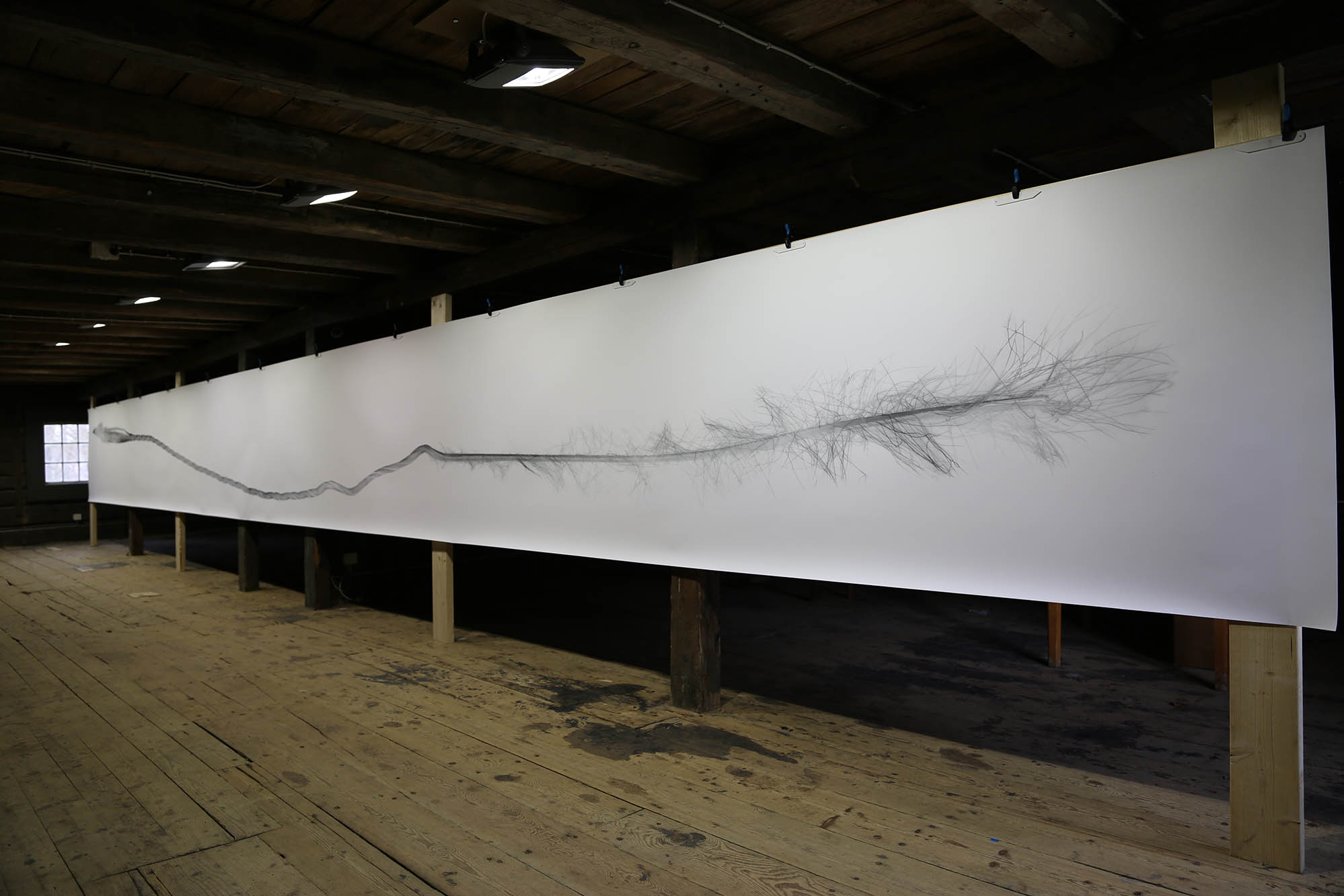

In a work, snaking its way across the Gallery floor, the interdependency and complexity of the saltmarsh habitat is indicated in several hundred ceramic tiles impressed with the names of animals, birds, insects, and plants that live in or frequent the marsh and contribute to its ecosystem. Some of these species, like the saltmarsh sparrow, seaside sparrow, and clapper rail are “obligates” that spend their entire life cycle in the marsh. Others breed in the marshes and elsewhere, and may survive the loss of saltmarshes. Still others come to feed in the rich environment of the marsh. The artists make visible the richness of species that thrive in the saltmarsh, out of view of urban dwellers. They quantify the variety of plants, insects, birds, and animals that will be lost or displaced when rising waters overtake and flood the marsh.

***

At Jacob’s Creek, the artists watched as Robinson and Reinert carefully captured the birds in mist nets and quickly took measurements of their health, banded their legs for future tracking, before releasing them. There is something magical about the moment of release, when the bird is freed and lifts off from the hand of the researcher. It stems from the encounter of two species in unusually close proximity, and from the release of anxiety in both bird and human as the encounter ends. Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilsonhave captured this moment in a series of photographs that they describe as an “homage to the carers of the birds.”[9]While the photographs are that—a recognition of the humans who truly see and care for other species—they also carry darker implications. For here, the artists present us with an unrecognizable landscape. Colors have shifted to eerie, otherworldly hues: grasses are a mixture of navy and magenta, the sky an odd grey-pink. Making this shift, the artists definitively remove their images from the realm of documentary or environmental photography. Images that would otherwise read as sweet and wistful, take on an ominous and dystopic air. This manipulation in color forecasts our future world, in which the birds that disappear off the edge or out of the frame of the photos are no longer simply escaping our grasp; they are instead exiting our world.

Viewers to the exhibition will have noted the lack of representative images of our ostensible subject: the saltmarsh sparrow. Reinforcing the theme of “searching” and referencing the extinction of the bird, the artists offer only one such view and position it as the culmination of our viewing experience. A bird blind, traditionally used for viewing and study, sits at the rear of the gallery; through the window in the blind we observe athree-dimensional likeness of a saltmarsh sparrow. Perched on a branch, the life-size bird ruffles her feathers as she observes her surroundings (the marsh or us). The artists draw attention to the reversal of roles, of the bird observing us or alternately of our attempting to look out through the eyes of the bird. The illusion is created via the theatrical technique called “Pepper’s ghost,” which employs a mirror to “throw” an image into view. The image is fleeting. Reduced to a ten secondoop that the artists liken to a “relic” – a future object of remembrance.[10]

***

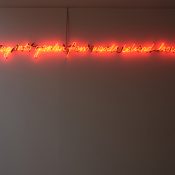

The extinction of the saltmarsh sparrow is foretold. We have experienced this before with Martha the passenger pigeon who died in the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914, with Lonesome George the last known Pinta Island tortoise of the Galapagos Islands who passed on June 24, 2012, and with multitudes of less famous examples of species collapse. In this period of extraordinary and human-generated changes to our environment, how should we respond to the loss of this small, somewhat hidden, and un-iconic bird, whose existence may seem insignificant to those humans who are neither biologist, environmentalist, nor even, avid birder? For Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson, the answer is clear:

“When the extinction of a species occurs, it is neither enough nor appropriate to close ranks and ‘carry on regardless.’ We should learn to grieve and through that process come to an understanding of how it is we are changed — and how it is we should go on.[11]

“As artists, we consider art to be both the most promising platform and the most likely instrument by which . . . traditionally discrete knowledge-fields will [combine to] succeed in effecting significant and increasingly urgent cultural and behavioral change.

And change is the only show in town.”[12]

Jo-Ann Conklin

Published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name

April 6 to July 7, 2019

©David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University

Titles: The Only Show in Town

Elevation #1:escape/release/escape 1–5

Elevation #2:moon/wake/moon/wake/moon/wake

Elevation #3:Salicornia depressa

Elevation #4: flood/wave/flood

Elevation #5: hide/blind/hide

Elevation #6: the ebbing

[1]Research for The Only Show in Townwas conducted over a two-year period (2017–2019).

[2]“According to SLAMM [Sea-level Affecting Marshes Model] project maps, Rhode Island is poised to lose 13 percent of its marshes with one foot of sea-level rise; 52 percent of marshes with three feet of sea-level rise; and a staggering 87 percent of its marshes with five feet of sea-level rise.” http://www.crmc.state.ri.us/news/2017_1016_wc_rssm.html.Estimated projection from NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] forecast sea-level rise of nine to eleven feet by 2100, foretelling the demise of RI saltmarshes.

[3]The results of Reinert and Robinson’s study are not encouraging. Of the twenty-seven nests that were monitored in 2018, only nine nests were successful in fledging at least one chick. More than half of the nests were lost to flooding. 2017-2018 Summary: Breeding Ecology of Saltmarsh Sparrows (Ammodramus caudacutus) in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island.https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hvEXL2TqKIsV6gUnY_jNmvviV0ITA2Ox/viewaccessed 2/15/19.

[4]Email correspondence with artists, 9/27/18.

[5]Ibid.

[6]Ibid.

[7]James H. Wandersee and Elisabeth E. Schussler, “Toward a Theory of Plant Blindness,” in Plant Science Bulletin, Spring 2001. https://www.botany.org/bsa/psb/2001/psb47-1.pdfaccessed 2/15/19.

[8]Artists’ website, Beyond Plant Blindness.https://Snæbjörnsdóttirwilson.com/category/projects/beyond-plant-blindness/accessed 2/1/19.this quotation from the team behind the Swedish-based project Beyond Plant Blindness(2015-17) of which Snæbjörnsdóttir Wilson were the artist contributors.

[9]Conversation with the artists, 1/25/19.

[10]Email from the artists, 2/24/19.

[11]BryndísSnæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson, “Other Stories ..On Power and Letting Go,” in You Must Carry Me Now: The Cultural Lives of Endangered Species, Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson, 284 Publishing Inc., Arizona State University Art Museum, 241.

[12]Email correspondence with artists, 9/27/18.