Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson’s 2018 series of works Shooting the Messenger (2018) takes as its leitmotif, the idea of the unwelcome visitor, arriving at the shores of an island. The visitor’s appearance in this place, though opportune, is not entirely voluntary and certainly not comfortable. In Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Marcus Coates’ Finfolk, Lars von Trier’s Dogville, the protagonist’s appearance, may be seen as the consequence of changed circumstance and possibly a harbinger of other more extreme events to come. Like them, with global warming, looming belatedly but ever more prominently in the media gestalt and so, in public consciousness, the arrival of polar bears in Iceland signifies a pivotal moment, in its potential to trigger either (temporally) new (or historically repetitive) behaviours in the host, with equally far reaching consequences.

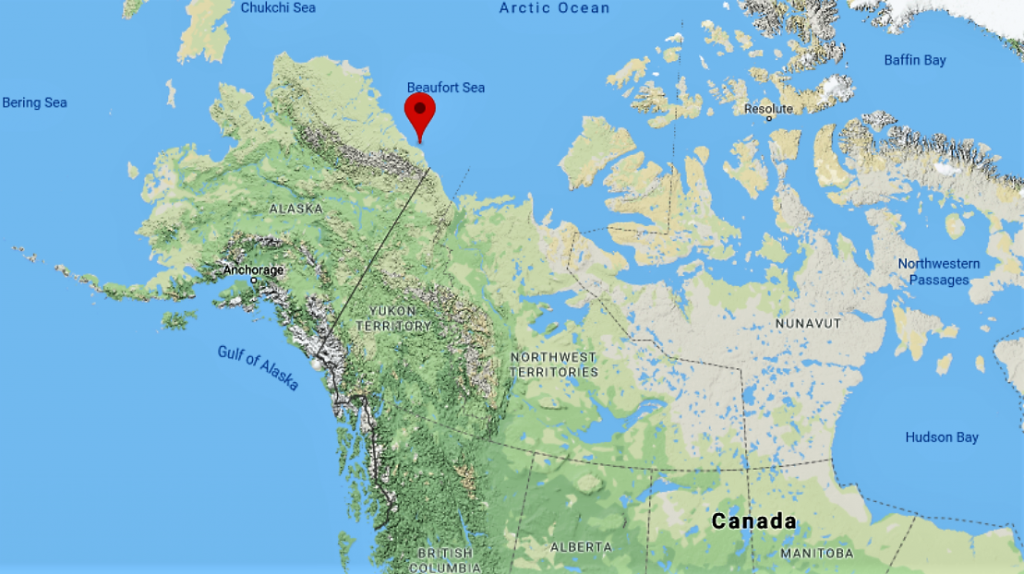

In the summer of 2008, two polar bears made respective appearances on the Skaga peninsula, (Skagaströnd) in the north of Iceland, on the 3rd and on the 16th of June. Their arrival, though not at all extraordinary in itself, caused a particularly public reaction and controversy.

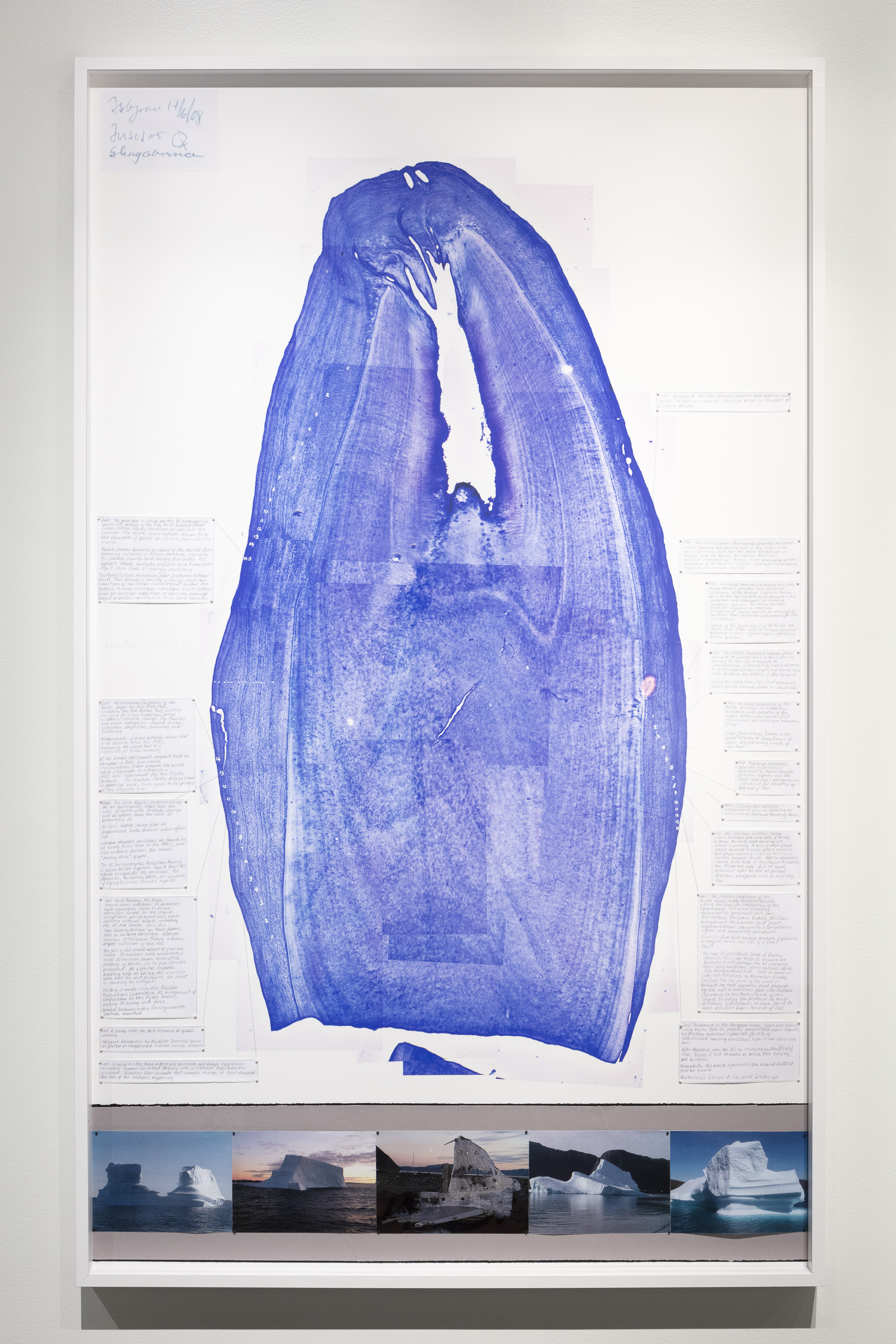

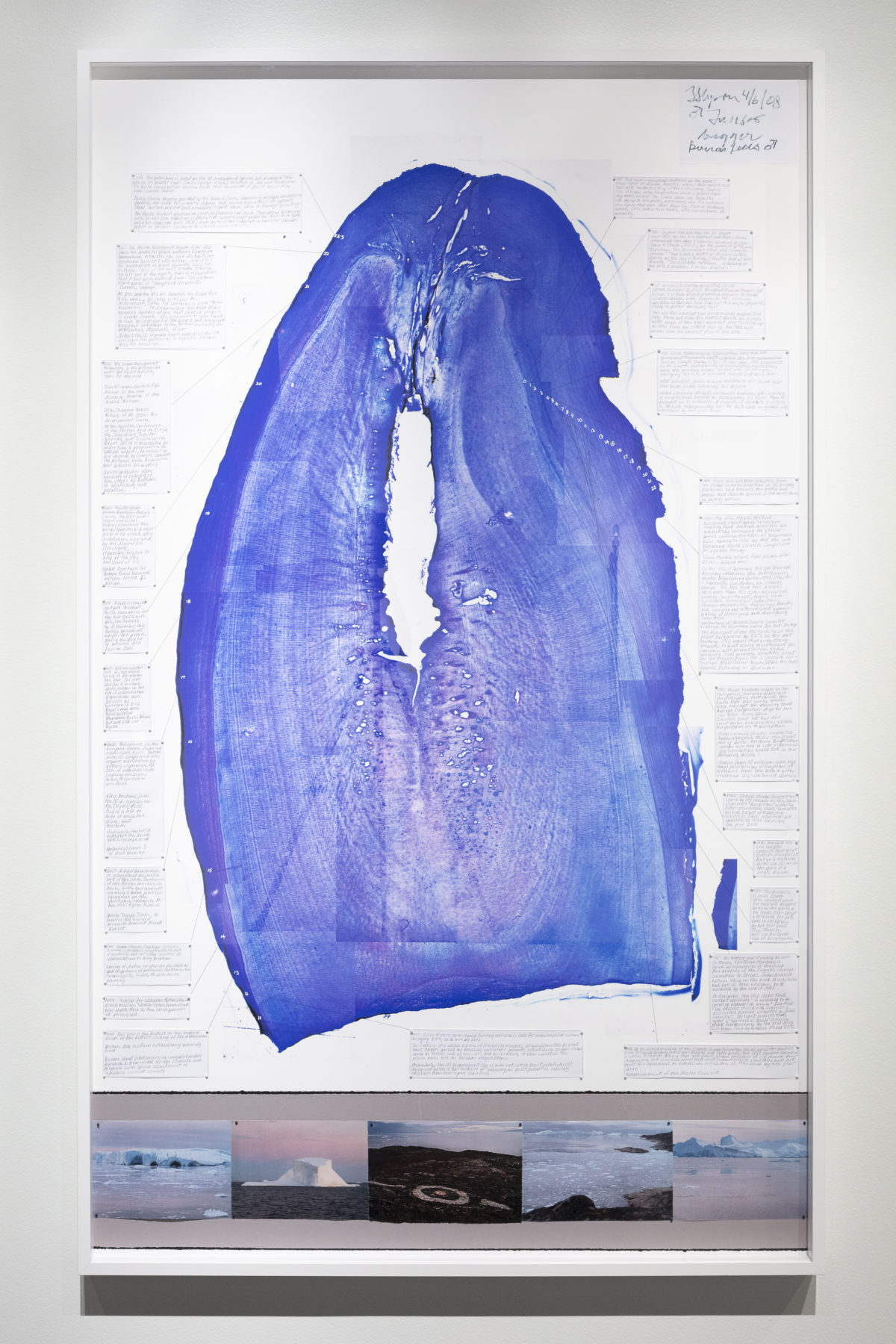

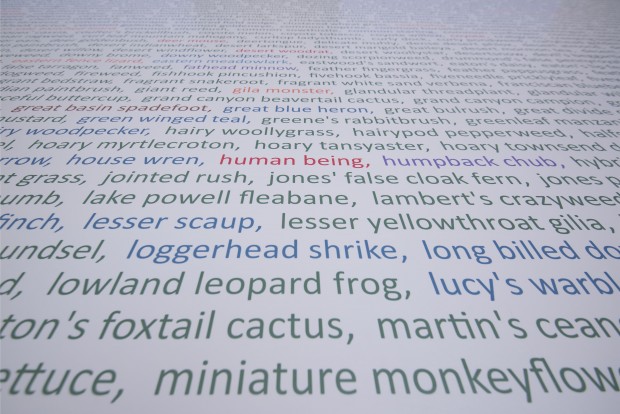

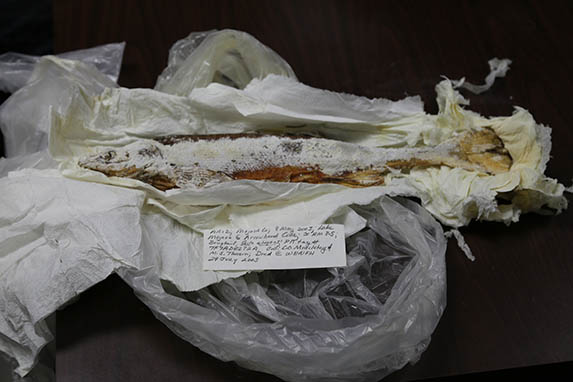

In response, for Anchorage Museum, last year, the artists made a two-part work entitled Shooting the Messenger in which a cross section of one of each bear’s teeth indicating annual, cementum-layer growth, was set against a roster of climate change events, summits and warnings correspondent with those same years of each bear’s life.