Matrix: Series # 1 (The View From Up Here, Anchorage Museum 2016

Matrix: Series # 1 (The View From Up Here, Anchorage Museum 2016

Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson

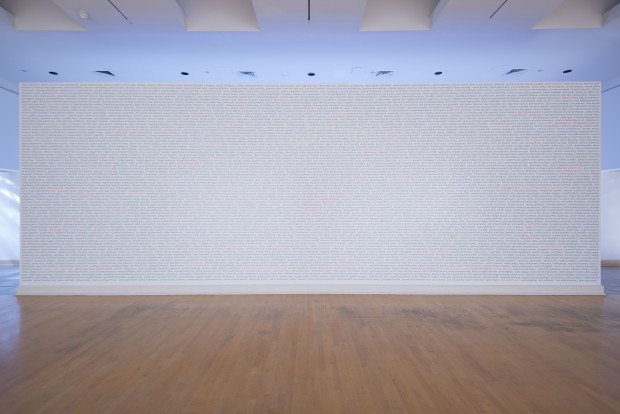

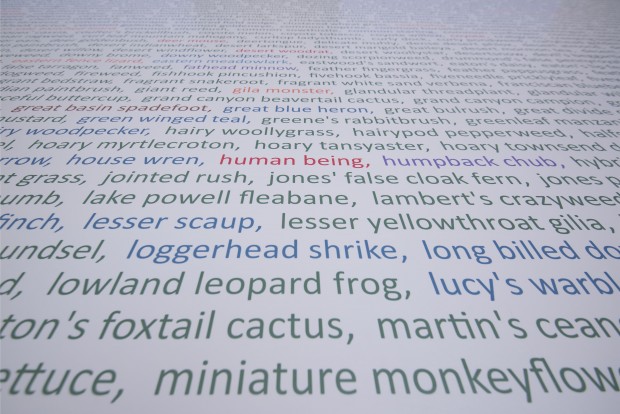

Barrow and the North Slope Borough is a place where human interests of many kinds intersect. With the National Petroleum Reserve Alaska to the West and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to the east, and Prudhoe Bay between them, without obvious correspondence, such interests coalesce with those of other species within a crucible of environmental contention.

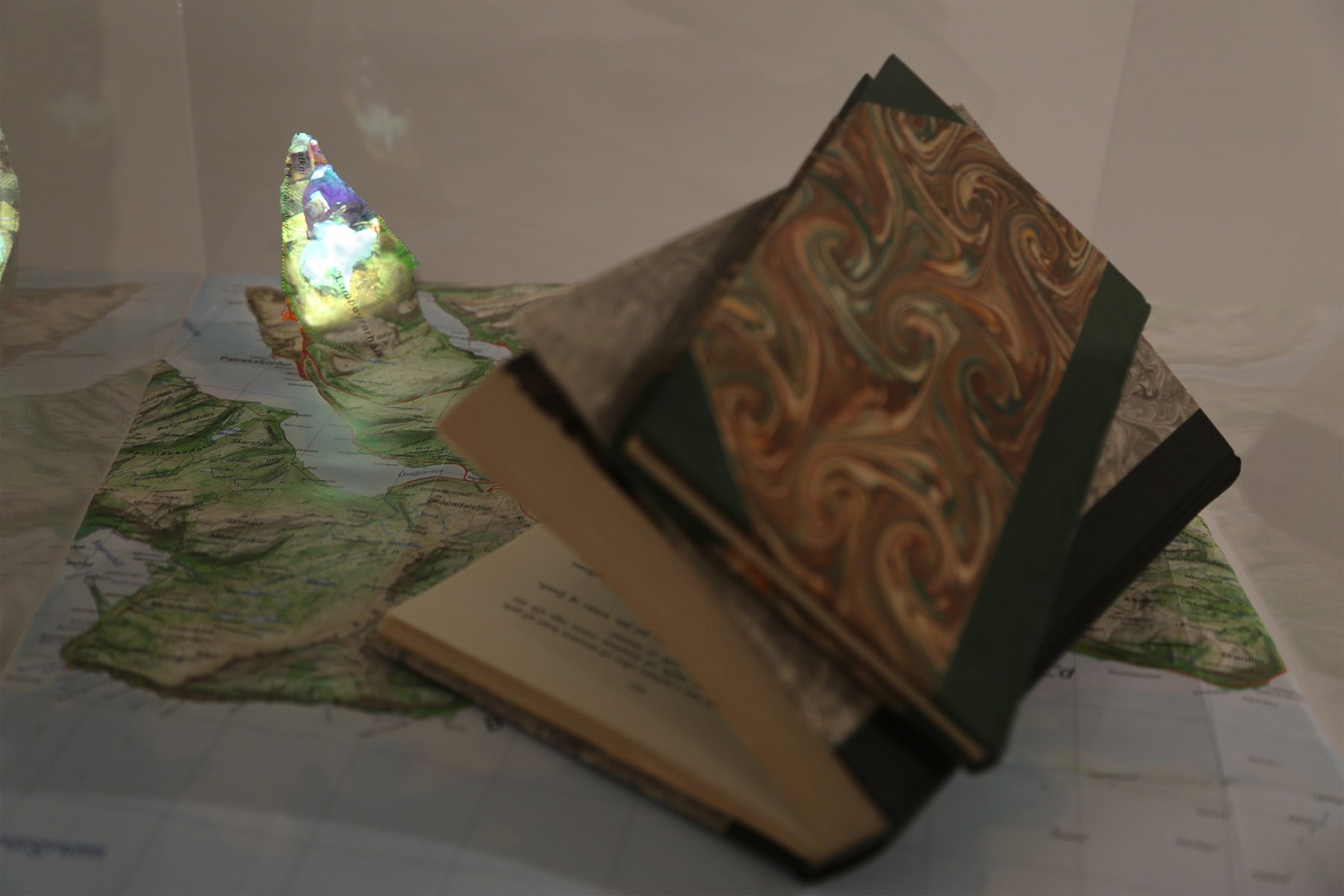

For many years, as artists we have been fascinated by the individuality and ergonomics of polar bear maternity dens – their allure as places of beginning and of continuity and how, as such, they embody both a biological specificity of purpose and (to us) a cultural/environmental register of touching significance.

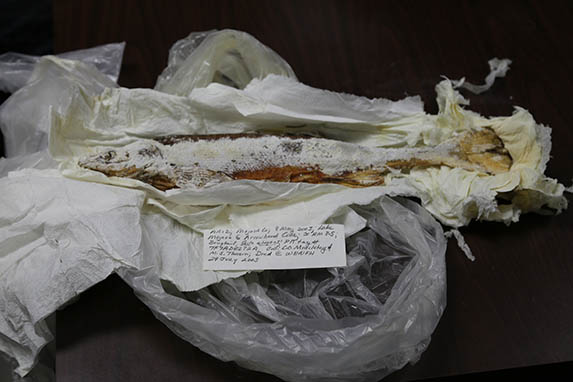

Having over the last six years, researched the unique iterations of denning, first in ‘wilderness’ areas in Svalbard and Greenland, far from human presence, we find that in the Alaskan arctic the National Geographic narrative of pristine isolation and environmental perfection is misleading… out there polar bears share the terrain with a complex human matrix comprising the Inupiaq people*, the oil industry, the tourist industry and a legion of environmental scientists. As a consequence bears will often den in close proximity to human sites.

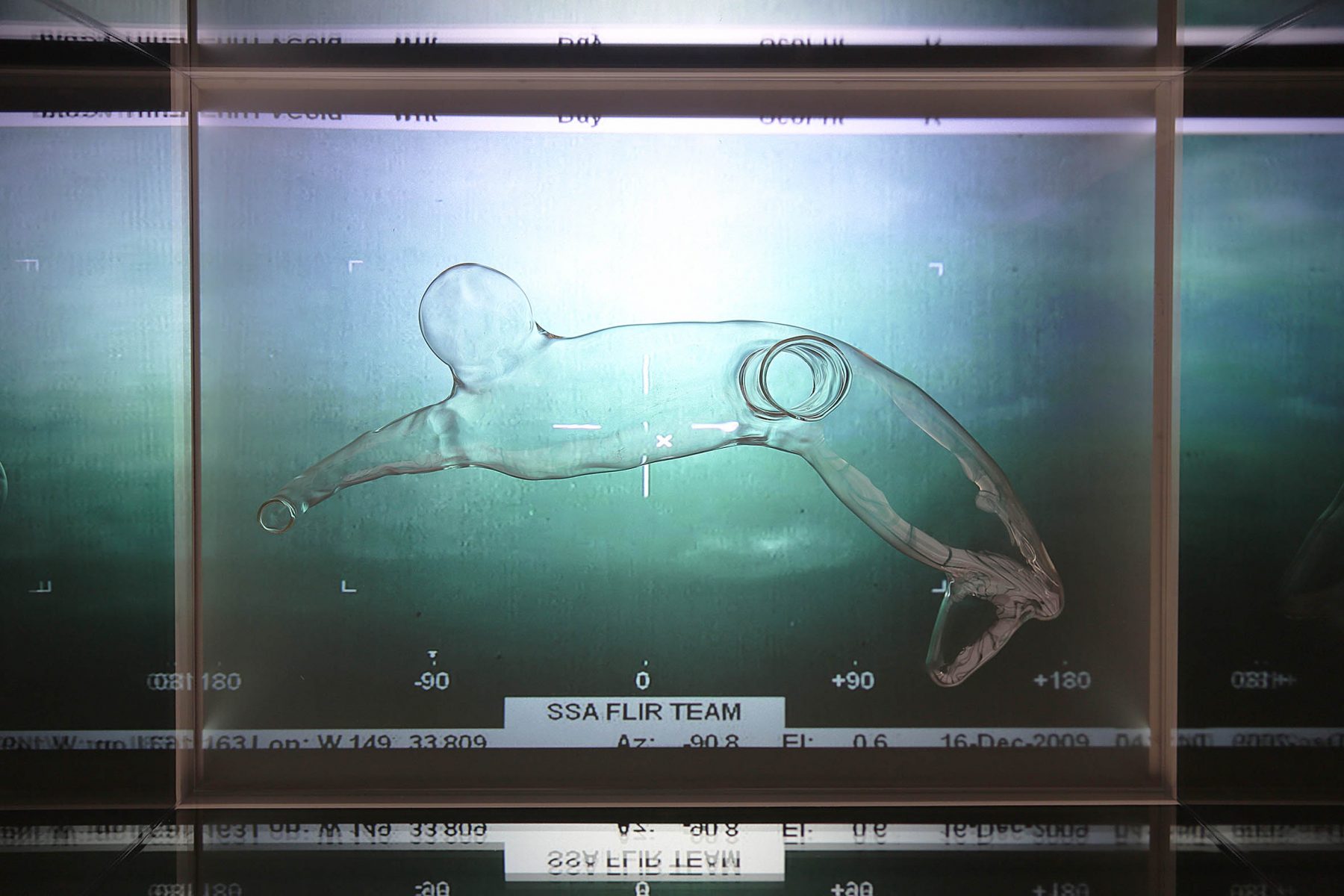

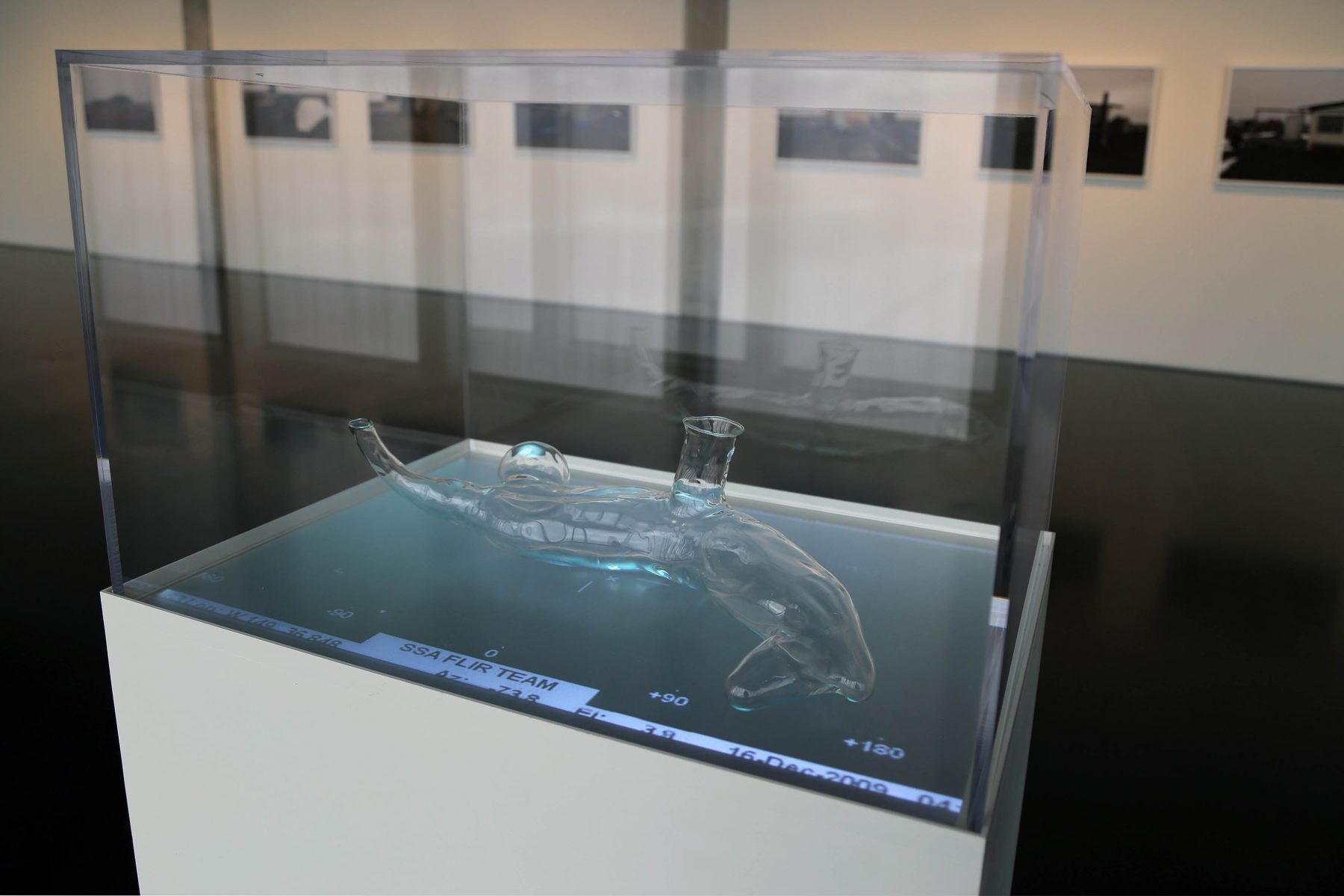

Nevertheless, the oil industry is obliged to use its technology and resources including FLIR (Forward Looking Infra Red) thermal imaging in order to assist in locating the sites of denning bears during the preparation of ice roads each winter. The discovery of dens by these means can determine routes or prompt diversions.

Just south of Point Barrow within a mile of the most northerly place on US soil, there exists a last scattering of makeshift shelters and houses – seasonal human dwellings in various states of disrepair, to which townsfolk too migrate in the summer.

*Inupiaq people have an ancient relationship with the polar bear, its habits and behaviours and despite now sharing the location with incomers from over 30 nations, maintain hunting traditions, using the animal as a source of food and clothing.

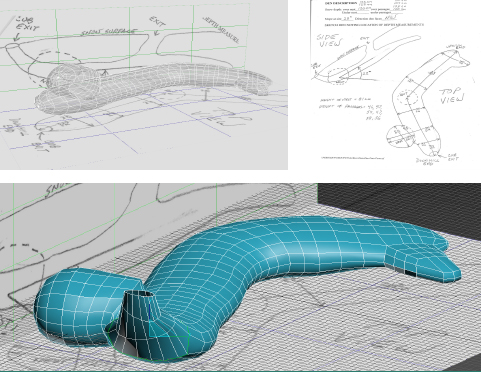

the glass maquettes were made with the assistance of Max Robertson (University of Cumbria, 3D modelling) and Brian Jones (Wearside Glass, National Glass Centre, Sunderland UK – with financial assistance from the University of Sunderland)

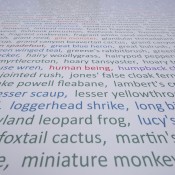

During the last decade the image of the polar bear has moved in the public imagination from being an icon of strength, independence and survival in one of the most climatically extreme of world environments, to that of fragility, vulnerability and more generally of a global environmental crisis.

During the last decade the image of the polar bear has moved in the public imagination from being an icon of strength, independence and survival in one of the most climatically extreme of world environments, to that of fragility, vulnerability and more generally of a global environmental crisis.

Matrix is an ambitious project, begun inthe Spring/Summer of 2010 with a residency in Longyearbyen, Svalbard where we focused on polar bear dens as the perfectly adapted model for habitat in the arctic environment.

The Polar Bear species is under threat from global warming, largely through the depletion of ice and shortened winters. Through discussion with experts in the field, empirical enquiry and ultimately, art-driven initiatives we looked for examples of adaptation to changing environmental circumstance as a basis for contemplation and the re-appraisal of accepted knowledge. We are particularly interested in the architecture of specific dens, and their functionality and capacity for modification during use, in response to changes in local weather and temperature.

On our recent visit to Alaska, we visited with biologists working with oil companies to minimise disturbance of denning sites on the North Slope.