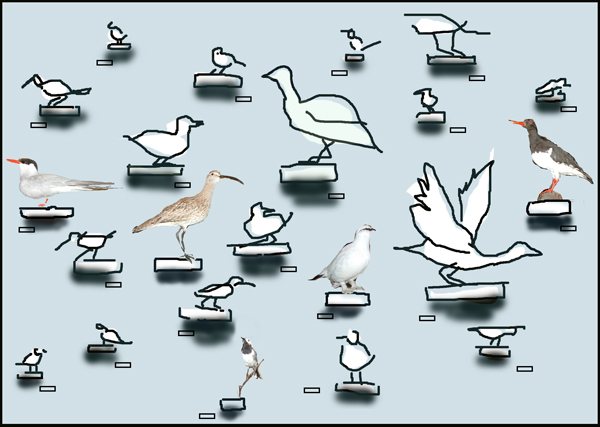

For Íslenskir Fuglar we look at human ambivalence regarding ideas of change. On the one hand we are conservative and suspicious of the disruption that change inevitably means. On the other we are drawn both to spice and novelty and to the practical benefits that some new introductions to our lives can bring. The judgment we make here between what we consider to be manageable and controllable and what we deem to be too disruptive and problematic is one that is fraught with potential miscalculations and unseen ramifications.

Long-term ramifications, touch at least obliquely, on the ecological and environmental consequences of human taste, fashion and favouritism – see for instance Mark Dion’s Survival of the Cutest –and this albeit wider interpretation is another reasonable reading of Islenskir Fuglar.

Commissioned for the exhibition Bæ Bæ Iceland (2007) the artists considered issues of nationality and nationhood, particularly in relation to changing populations. Iceland has traditionally fostered notions of cultural purity and defiance in relation to language, the economy, customs and identity. Despite this, in the most unexpected quarters small, incremental allowances, unnoticed over the years, have created new sub-cultures that when considered together cannot help but be seen as constituting an assault on ideas of cultural permanence or immutability.

Something as apparently beneficial and reliable as a map or a guide, if it is to remain of any use must take into account these small changes and therefore over time will come to be a barometer of larger cultural shifts – it must be a document of how we present ourselves, practically and symbolically both to ourselves and to the visitor. Any map or guide designed to reflect the state of things must in these circumstances be subject to a programme of regular updates. It is by these means that we present ourselves, practically and symbolically both to ourselves and to the visitor, but increasingly this will be a snapshot rather than a lasting document.

In attempting to identify what has changed in us but what still may help to define the new ‘us’ it’s possible that paradoxically, we may usefully examine our taste for the exotic. By comparing the old with new representations it should be possible to gauge the larger cultural shifts and trends that have occurred and anticipate those that may yet come to pass. In this we can measure our tastes and desires. Fashions come and go but some desires will stand the test of time – are assimilated by us and come to permanently shape the way we see ourselves and the way we are seen by others. Definitions are meant to be definitive. What is definitive today however, may no longer be definitive tomorrow and in this work, Snæbjörnsdóttir/Wilson are particularly interested in speculatively re-configuring the parameters upon which such definitions might be drawn. It is an innocuous game but one with the potential to nibble at, erode and disturb the borders of past, present and future, of local and global, natural and cultural, of acceptability and taboo.

Exhibited at; Bæ, Bæ Iceland, Listasafn Akureyrar, Iceland (2007) Inbetween: Cabinet of Curiousities, Hafnarborg, Iceland (2011)

Radio Animal was a component of the project Uncertainty In The City – a speculative, artists’ exploration into the relationship between humans and the animals that nudge at and breach the borders of our homes.

Radio Animal was a component of the project Uncertainty In The City – a speculative, artists’ exploration into the relationship between humans and the animals that nudge at and breach the borders of our homes.![]()

![]()

![]()

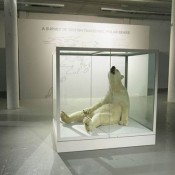

In our often belated attempts to steward, care for or ‘repair’ environments – when individual animals and animal populationas are transformed from beings and societies into data, what of consequence is really captured – and importantly, what is lost?

In our often belated attempts to steward, care for or ‘repair’ environments – when individual animals and animal populationas are transformed from beings and societies into data, what of consequence is really captured – and importantly, what is lost?